|

Retrospective Computed Tomography Scan Analysis of Percutaneously Inserted Pedicle Screws for Posterior Transpedicular Stabilization of the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine

Accuracy and Complication Rates

Darryl A. Raley, MBBS, BSc * Ralph J. Mobbs , BSc, MBBS, MS, FRACS* †

Study Design. Retrospective clinical data analysis.

Objective. To investigate the misplacement rate and related

clinical complications of percutaneous pedicle screw insertion in

the thoracic and lumbar spine.

Summary of Background Data. Percutaneous insertion of

cannulated pedicle screws has been developed as a minimally

invasive alternative to the open technique during instrumented

fusion procedures of the thoraco-lumbar spine. The reported rate

of screw misplacement using open techniques is well described,

however data is lacking on the exact failure rate of the percutaneous

technique.

Methods. A total of 424 percutaneously inserted pedicle screws

from 2007 to 2010 were analyzed in 88 patients, from a single

surgeon series (RJM). Axial reformatted computer tomographic

images were examined by 2 independent observers and individual

and consensus interpretation was obtained for each screw position. A

simple grading system was used for assessment of screw accuracy—

Grade 0: screw within cortex of pedicle; Grade 1: screw thread

breach of wall of pedicle < 2 mm; Grade 2: signifi cant breach > 2 mm

with no neurological compromise; Grade 3: complication including

pedicle fracture, anterior breach with neuro-vascular compromise,

and lateral or medial breach with neurological sequelae.

Results. The indications for percutaneous pedicle screw insertion

include: degenerative (78%), trauma (13%), tumour (8%), and infection (1%). Pedicle screws were inserted into level T4 to S1. The

most common levels performed include L4 and L5 with the most

common indication for surgery being an L4/5 spondylolisthesis. 383

out of 424 screws (90.3%) were placed in the cortical shell of the

pedicle (Grade 0). Forty-one screws (9.7%) were misplaced from

T4 to S1. Of these, the majority were Grade 1 pedicle violations

(24 screws; 5.7%), with 15 Grade 2 violations (3.5%) and 2 Grade

3 violations (0.5%). Of the 2 Grade 3 pedicle violations, both were

pedicle fractures but only 1 had associated neurological defi cit (L4

radiculopathy postoperatively).

Conclusion. Percutaneous insertion of cannulated pedicle screws

in the thoracic and lumbar spine is an acceptable technique with

a low complication rate in experienced hands. The overall rate of

perforation is below the higher rates reported in the literature for

the open technique. Complication rates including pedicle fracture

were low.

Key words: pedicle screw fi xation , posterior stabilization ,

computer tomography , minimally invasive surgery , lumbar spine .

Spine 2012 ; 37 : 1092 – 1100

From the * Prince of Wales Hospital, Randwick, Sydney, Australia ; and

† Sydney Spine Clinic, Sydney, Australia .

Acknowledgment date: April 8, 2011. First revision date: September 29,

2011. Acceptance date: October 1, 2011.

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical

device(s)/drug(s).

No funds were received in support of this work. One or more of the author(s) has/have received or will receive benefi ts for personal or professional use from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript: e.g. , honoraria, gifts, consultancies, royalties, stocks, stock options, decision making position.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Darryl Raley, MBBS, BSc,

9 Clematis Close, Cherrybrook, Sydney, NSW 2126; E-mail: darryl.raley@gmail.com

DOI: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31823c80d8

Spinal fusion using pedicle screws is a widely accepted

method for the management of a variety of spinal conditions

requiring stabilization. Traditional open techniques

for insertion of screws are associated with extensive

blood loss, lengthy hospital stays, and signifi cant costs.1

Minimally invasive techniques use small incisions and small

muscle splitting approaches, and are associated with less

blood loss, less soft tissue trauma, and less postoperative pain

than traditional open techniques.2–6 Many studies have investigated

the accuracy of screw placement by a conventional

open approach using simple radiograph, computed tomographic

(CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging,7–12 with

reported rates of screw misplacement up to 40%. 7 However,

there is a paucity of data on the exact failure rate of the percutaneous

technique. In this article, we focus on the accuracy

by 1 surgeon of purcutaneous pedicle screw placement

and introduce a simple grading system for CT evaluation of

pedicle screw placement. The purpose of our study was to defi ne the incidence of pedicle misplacement and compare it

with published data on open and percutaneous pedicle placement

techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 2007 and mid-2010, 88 consecutive patients

(47 men and 41 women) were analyzed after external transpedicular

screw fi xation of the thoracic, lumbar and sacral

spine (from T4 to S1). All patients had a CT performed

within 24 hours of surgery and fi lms entered into a database

for review. The age range of the patients was 9 to 85 years

(mean, 63 yr). The operations were performed at The Prince

of Wales Public and Private Hospitals, Sydney, Australia.

Surgical Procedure

All surgical procedures were performed by a single spine

surgeon (RJM). A total of 424 screws were implanted in 88

patients undergoing percutaneous thoracolumbar or lumbosacral

stabilization using the Serengeti spinal system (K2M,

Leesburg, VA, USA). Percutaneous pedicle screws ranged in

diameter from 4.5 to 7.5 mm and were inserted in accordance

with the technique described by Wiesner et al.13

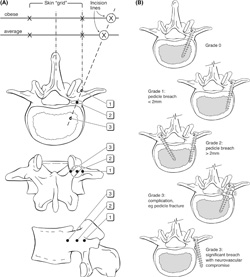

A brief description of this technique follows (Figures 1 , 2 ):

- The image intensifi er (II) is placed in the AP position. The

spinous process should be midline between the pedicles

to ensure a direct AP projection ( Figure 2 A).

- The position of the lateral aspect of the pedicle is marked on

the skin. Depending upon the depth of the tissue between

skin and pedicle, the skin incision should be made lateral

( Figure 1 A) so that appropriate angulation of the Jamshidi

needle can be made when inserting into the pedicle.

- The Jamshidi needle is placed through the skin incision

and “docked” onto the lateral aspect of the pedicle

(Figures 1 A, 2 ). This is called the “3 o-clock” position.

- The Jamshidi needle is advanced 20 to 25 mm into the

pedicle through the cortical bone, making sure the needle

remains lateral to the medial pedicle wall (Figures 1 A, 2 ).

A second Jamshidi needle can then be placed on the contralateral

side in a similar fashion.

- The II is then positioned in the lateral plane. The Jamshidi

needle should now be in the vertebral body, and therefore

“safe” with no risk of medial pedicle breach (Figures 1 A, 2 ).

- The stylet is then removed and a Kirschner (K)-wire is placed down the barrel of the Jamshidi needle. Once a

satisfactory penetration of the pedicle with the K-wire is

completed, the Jamshidi needle is removed, taking care

to maintain the position of the K-wire. A cannulated

scalpel is then passed over the K-wires to provide accurate

incisions that are long enough for the tissue guard.

- Tissue guards are then placed over the K-wires to perform

soft tissue dissection down to the level of the bone.

A pedicle screw tap is then placed down the trajectory

of the K-wire, through the pedicle into the trabecular

bone of the vertebral body, taking care the K-wire is not

moved during introduction ( Figure 2 ).

- The tap is then removed and the appropriate pedicle

screws (measurements based on preoperative CT scans)

are placed down the K-wire ( Figure 2 ), making sure not

to advance the K-wire beyond the anterior aspect of the

vertebral body. Confi rmation of pedicle screw placement

is achieved with II.

- The rods are then inserted via the pedicle screw incision

sites and join the pedicle screw heads. A dedicated reduction

device can be used with the retractor sleeves for

correction of a spondylolisthesis.

- The retractor sleeves are then removed

- All wounds are then closed via a standard method.

Figure 1. (A) Diagrams illustrating the

anatomical principles of percutaneous

pedicle screw insertion: views from top to

bottom: superior, posterior, lateral, superior.

First the initial skin incision is

made with the patients’ body habitus in

mind. Second, the Jamshidi needle is fi rst

‘‘docked’’ onto the lateral aspect of the

pedicle — ‘‘position 1’’ — on the anterior/

posterior image intensifi er (II) radiograph

projection. Third, the Jamshidi needle is

advanced 20 to 25 mm so that the needle

is beyond the medial border of the pedicle

and into the vertebral body – to ‘‘position

3.” Finally, the position is confi rmed by

lateral II radiograph projection before insertion

of the K-wire. (B) Grading system

for evaluation of screw position.

Postoperative CT was obtained for all patients to assess

implant position, using a GE 16 slice Brightspeed unit with

0.625 mm slices acquired in helical mode in a craniocaudal

direction.

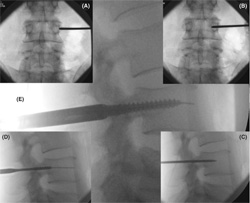

Figure 2. Percutaneous Technique (L4 Pedicle).

(A) Using AP x-ray, the Jamshidi needle

is ‘docked’ onto the facet/TP junction. (B)

The needle is advanced 20 to 25 mm making

sure that the tip of the Jamshidi is not beyond

the medial pedicle border. (C) Lateral

x-ray confi rms that the Jamshidi is within the

vertebral body. (D) Tapping the pedicle. (E)

Insertion of pedicle screw.

Evaluation of Screw Position

Two independent observers analyzed digital axial CT slices

of all instrumented pedicles, with individual and consensus

interpretation for each screw. A simple grading system

(Mobbs Raley) was devised for evaluation of screw position

( Figures 1 B, 6 ).

The grading system was devised to indicate accuracy of

placement (Grade 0, 1, 2) and a signifi cant complication with

the technique (Grade 3) that was likely to require revision

surgery ( Table 1 ).

The direction of the pedicle violations was noted, and

the degree of the screw malalignment in the axial plane was

measured. The transverse screw angle was determined by

measuring the angle between a line parallel to the vertebral

midline and a line through the center of the screw tract,

and was measured for all pedicles that showed a screw

displacement.

| TABLE 1. Grading System for Evaluation of

Screw Position |

| Grade 0 |

Screw within cortex of pedicle |

| Grade 1 |

Screw thread breach of wall of pedicle: ≤ 2 mm |

| Grade 2 |

Significant breach: > 2 mm. No neurological

compromise |

| Grade 3 |

Complication: pedicle fracture, anterior breach

with neuro-vascular compromise, lateral/medial

breach with neurological sequelae |

K-wire Complication

A serious potential complication can arise from insertion of

the K-wire beyond the anterior aspect of the vertebral body

( Figure 7 ). This can either occur from aggressive advancement

of the K-wire down the barrel of the Jamshidi, osteoporotic

bone with poor tactile feedback when inserting the

K-wire, or with the K-wire inadvertently moving distally

with advancement of the pedicle tap.

There are no reports in the literature that discuss complication

rates from anterior placement of a K-wire at the

time of percutaneous pedicle screw placement. All cases of

anterior placement of K-wires were prospectively recorded,

and any subsequent complications noted such as blood loss

or ileus.

Radiation Exposure

Mean operative time and mean fl uoroscopy time was

recorded for the fi rst and last 5 patients in the series receiving

single-level fusion (4 pedicle screws), to extrapolate surgeon

radiation exposure, and to demonstrate the learning curve

associated with the technique. In addition, mean radiation

exposure (mGy) to the last 5 patients receiving single-level

fusion was obtained from a standard measurement of output

from the C-arm of the image intensifi er. The C-arm was

in the source inferior position for all cases. Only single-shot

pulsed imaging was performed.

Statistical Analysis

The chi squared method and Fisher exact test (2-tail) was

used to determine signifi cant differences in the number of

screw malpositions, the direction of screw misplacement, and

corresponding angulation. In addition, because only a small

number of screws were placed at the thoracic levels, the pedicles

of T4 to T12 were combined and analyzed separately

as thoracic pedicles. Among the lumbar vertebrae, tests for

equal proportions were used to determine if there was a tendency

for lateral or medial pedicle violations and, for those

with a lateral pedicle violation, if this was due to incorrect

angle of insertion. The signifi cant difference level was set at

P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using R-2.11.1

(R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

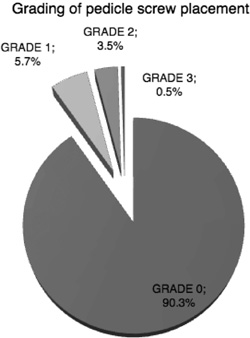

A total of 424 percutaneously inserted pedicle screws were

analyzed in 88 patients, and 383 screws (90.3%) were placed

in the cortical shell of the pedicle (Grade 0). Only 41 screws

(9.7%) were misplaced from T4 to S1. Of these, the majority

were Grade 1 pedicle violations (24 screws; 5.7%), with 15

Grade 2 violations (3.5%) and 2 Grade 3 violations (0.5%;

Figure 3 ). There were 30 lateral and 11 medial pedicle cortex

violations ( Table 3 ). At the lumbar level there were signifi

cantly more lateral (n = 26) than medial (n = 7) cortical

violations ( P = 0.00094), whereas at the thoracic level there

was no difference.

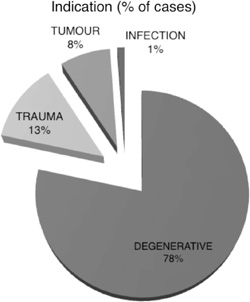

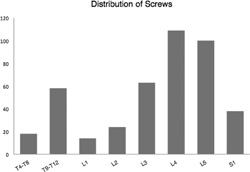

The indications for screw insertion were predominantly

degenerative (n = 69, 78%), and included trauma (n = 11,

13%), tumor (n = 7, 8%), and infection (n = 1, 1%; Figure 4 ). The distribution of screw misplacements with respect to the

vertebral level is shown in Table 2 and graphically in Figure 5 .

There were no signifi cant differences within the lumbar vertebrae,

with failure rates between 4% (L2) and 16% (L3),

P = 0.6134. Combining thoracic levels T4 to T12, there

were no signifi cant differences compared with lumbar pedicle

screw misplacements (9.2% and 9.5%, respectively,

P = 0.8746). We found no correlation between the operated

level and screw malpositioning.

The transverse pedicle angle was measured for all misplaced

screws ( Table 2 ). Considering the direction of the

screw malalignment and the difference between the screw

and pedicle angle, 18 of the 41 pedicle violations (43.9%)

could be attributed to wrong angle of insertion. Of the lateral

cortical violations at the lumbar level (26 of 33 misplaced

screws), 13 (50%) could be attributed to incorrect angle of

insertion ( P = 0.8450).

There were 2 Grade 3 pedicle violations (patient 31 and

49, respectively, Table 2 ). One was a pedicle fracture without

neurovascular compromise; the other was a pedicle fracture

with L4 nerve injury (L4 radiculopathy postoperatively).

Both Grade 3 pedicle violations were performed early in the

series (within the initial 10 patients operated on).

There were 4 anterior K-wire perforations (0.9% of all

screws) during the course of the study period. One case was

because of advancement of the K-wire at the time of tapping

the pedicle, 2 cases were because of osteoporotic bone with

poor tactile feedback for the surgeon and 1 case of forceful

advancement of the K-wire with anterior puncture of the

vertebral body ( Figure 7 ). From the 4 cases identifi ed with

K-wire perforation, 1 patient had a small volume retroperitoneal

bleed and ileus treated conservatively. The other 3

patients had an uneventful recovery postoperatively.

Mean operative time was 238 minutes for the fi rst 5

patients, and 147 minutes for the last 5 patients receiving

single-level fusion (4 pedicle screws). The mean fl uoroscopy

time was 1.71 minutes for the fi rst 5 single-level cases (0.43

min/screw), and 0.76 minutes for the last 5 single-level cases

(0.11 min/screw). Mean maximum patient exposure for

these last 5 cases, measured from the output of the C-arm,

was 44.9 mGy (range 26.8–58.1 mGy).

DISCUSSION

The accuracy of pedicle screw placement using the traditional

open technique has been the subject of several imaging

studies. However, the reported misplacement rates have been

very different, ranging from 8% to 40%.7,14 This is partly

due to the lack of image guidance and the variation in pedicle

placement assessment methods including the defi nition of

misplacement.

Evaluation of percutaneous screw insertion for temporary

external fi xation (a diagnostic tool) with fl uoroscopic guidance

has been undertaken using a human cadaver model.13

The reported overall perforation rate of the dissected specimens

was 10% (mainly medial). In a separate study the same

authors evaluated screw position of percutaneous external

fi xation using axial CT images, with 51 patients and 408 pedicle screws.15 They reported a screw perforation rate of

6.6% (mainly medial and more often affecting the S1 pedicles).

Despite the screws used being noncannulated, this was

the fi rst study to analyze the accuracy of percutaneous transpedicular

screws. From recent publications on small series

of percutaneously inserted cannulated pedicle screws under

fl ouroscopic guidance,2,4,16–18 only 2 addressed the accuracy

of screw positioning. The smaller group was comprised of

only 3 patients with a single perforated screw.4 A somewhat

larger series (15 patients with a total of 60 screws),

reported an overall rate of screw perforation of 23% with

an incidence of severe frank pedicle penetration of 3.3% as

seen on axial images.18 The larger series to date reporting

results of percutaneous fi xation does not provide information

on screw placement. However, the reoperation rate

reported due to screw misplacement was 4% in that study

(2 of 49 patients).17

Figure 3. Pie chart showing the number of pedicle screws (%)

at each grade.

In our group of 88 patients with a total of 424 screws the

overall rate of screw perforation was 9.7% (41 screws) with

an incidence of severe frank pedicle penetration of 0.5% (2 of

424 screws) as seen on axial images. The incidence of screw misplacement in our series falls well within the reported rates

for the open technique, ranging from 8% to 40%,7,14 as well

as those reported for the percutanoues technique (6.6% to

10%, and up to 23%13,15,18). The neurological injury incidence

of 0.5% falls well below reported incidences ranging

from 2%19 to 5%, and even as high as 16.6%.7 Both Grade 3

pedicle violations occurred early in the series (within the fi rst

30 patients operated on), indicating a steep learning curve for

the percutaneous technique.

It should be pointed out that the rates of misplacement

vary according to the defi nition of misplacement and the

assessment method used. One study using CT assessment

of pedicle screw placement defi ned misplacement as the

position of the central axis of the screw out of the outer

cortex of the pedicle wall seen in axial CT images.20 On our

grading scale this would correspond to a Grade 2 or Grade

3 and underestimate the true misplacement rate (interestingly,

the authors reported an 8.2% frank misplacement

rate which was similar to our overall rate of screw perforation).

We included every single cortical encroachment by a

screw in the axial plane ( Figure 6 ). It could be argued that

such a screw position as that shown in Figure 6 (B) should

not be regarded as misplacement, and it could be that other

studies have not included such examples in their misplacement

reporting.

Figure 4. Pie chart showing indications for transpedicular fi xation

(% of cases).

| TABLE 2. Distribution of Pedicle Screws |

| Level |

Number of Screws (%) |

Misplaced Screws (%) |

Grade 0 |

Grade 1 |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

| T4–T8 | 18 (4) | 3 (7.3) | 15 | 0 | 1 (T4), 2 (T7) | 0 |

| T9–T12 | 58 (14) | 4 (9.8) | 54 | 1(T11) | 2 (T9),1 (T10) | 0 |

| L1 | 14 (3) | 1 (2.4) | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| L2 | 24 (6) | 1 (2.4) | 23 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| L3 | 63(15) | 10 (24.4) | 53 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| L4 | 109 (26) | 11 (26.8) | 98 | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| L5 | 100 (24) | 10 (24.4) | 90 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| S1 | 38 (9) | 1 (2.4) | 37 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 424 | 41 (9.7) | 383 | 24 | 15 | 2 |

CT examination provides more information than plain

fi lms, but has obvious limitations. Wiesner15 examined CT

images of screw tracts for cortical wall defects after screw

removal, and reported a low perforation rate of 6.6%.

However, in our study, CT assessment of pedicle placement

was complicated by image artifacts caused by the in vivo

screws. Although clearly a limitation of this study, it could

be thus argued that screw placement in our study may have

greater accuracy than demonstrated by CT examination. A

major limitation of this study is that CT images were examined

in axial sections only. Schizas et al18 showed a lower

incidence of screw perforation in axial images compared

with coronal reconstructions. Thus it could be that the true

incidence of misplacement is higher when CT images are

screened critically including coronal views.

The analysis of the direction of screw misplacements

showed that there were signifi cantly more lateral than medial

pedicle violations at the lumbar levels and half of these could

be attributed to incorrect angle of insertion. This may be

explained by an increasing medial inclination of the pedicle

in the transverse plane from L1 (17 ° –25 ° ) to L5 (26 ° –40 ° ).21

In 1992, Gunzburg et al22 published the results of a radiographic

study in which they found the anatomical pedicle

center lies slightly more lateral than the pedicle shadow.

Initially in the series the starting point for the Jamshidi

needle would be the center of the pedicle on an AP x-ray.

This has the disadvantage that as the Jamshidi needle is

introduced further into the pedicle, the risk of medial pedicle

breach is higher as the starting point of the Jamshidi is potentially

closer to the medial border of the pedicle. The surgeon

altered the technique so that the Jamshidi would be docked

at the very lateral aspect of the pedicle ( Figures 1 A, 2 ), so that

with advancement of the Jamshidi, the risk of medial breach

is reduced. Thus, the accuracy of pedicle screw placement in

this study could potentially be improved by a more lateral

cannulation point with an emphasis on medial inclination.

Prospective analysis of K-wire complications revealed 4

anterior breaches ( Figure 7 ). There is minimal data in the literature

on the potentially devastating complication of vascular and abdominal injury with this technique. The authors documented

all cases and any subsequent complications. There

was a single complication of retroperitoneal hemorrhage and

ileus that improved with conservative measures. The senior

author places all patients with anterior K-wire breach on

broad spectrum antibiotics assuming there has been an intestinal

puncture. It is paramount that the senior surgeon remind

the assistant during the procedure that meticulous care be

taken with stabilizing the K-wire when multiple instruments

and the pedicle screw are placed over the guide K-wire.

The use of fl uoroscopic guidance for screw placement

results in potentially signifi cant radiation exposure to both

the surgeon and patient. Unfortunately, very little data exists

in the literature to help quantify this exposure. Bindal et al23

measured surgeon radiation exposure in minimally invasive

transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (with similar methods

for fl ouroscopic percutaneous pedicle screw placement),

using dosimeters placed at various locations. Their mean

fl uoroscopy time was 1.69 minutes per case, giving a mean

exposure of 76 mRem to the surgeon’s dominant hand, and

27 mRem to the waist under a lead apron. The mean fl uoroscopy

time in our series ranged from 1.71 minutes per case

for the fi rst 5 single-level cases, to 0.76 minutes per case for

the last 5 single-level cases. The maximum allowed annual

radiation exposure for radiation workers is 5 Rem to the

body and 50 Rem to an extremity.24 Extrapolating the data

from Bindal et al23 , on the basis of the mean fl uoroscopy

time at the end of our series, a surgeon would exceed exposure

limits to the torso after 417 single-level cases and to

the hand after 1471 single-level cases. Of course, multilevel

fusions require correspondingly more fl uoroscopy, and a

surgeon may also perform other interventional procedures

requiring fl uoroscopic guidance, such as vertebroplasty.

Annual dose limits could potentially be exceeded if a large

number of multi-level cases or other fl uoroscopically guided

procedures are performed.

| TABLE 3. Overall View of All Misplaced Pedicles |

| Patient |

Level |

Grade |

Direction of Misplacement |

Screw Angle |

Pedicle Angle |

Δ Angle |

Wrong Angulation |

| 22 | T4 | 2 | Medial | 27 | 7 | 20 | x |

| 22 | T7 | 2 | Lateral | 9 | 11 | –2 | |

| 22 | T7 | 2 | Medial | 24 | 17 | 7 | |

| 85 | T9 | 2 | Medial | 14 | 13 | 1 | |

| 87 | T9 | 2 | Lateral | 2 | 15 | –13 | x |

| 87 | T10 | 2 | Lateral | 13 | 14 | –2 | |

| 29 | 11 | 1 | Lateral | 1 | 12 | –11 | x |

| 37 | L1 | 1 | Lateral | 3 | 15 | –12 | x |

| 32 | L2 | 1 | Lateral | 2 | 13 | –11 | x |

| 2 | L3 | 1 | Medial | 11 | 8 | 3 | |

| 11 | L3 | 1 | Medial | 34 | 30 | 4 |

| 61 | L3 | 2 | Lateral | 8 | 21 | –13 | x |

| 31* | L3 | 3 | Lateral | 3 | 18 | –15 | x |

| 44 | L3 | 1 | Lateral | 10 | 11 | –1 | |

| 46 | L3 | 2 | Medial | 12 | 12 | 0 | |

| 46 | L3 | 2 | Lateral | 10 | 12 | –2 | |

| 65 | L3 | 1 | Lateral | 10 | 12 | –2 | |

| 75 | L3 | 1 | Medial | 1 | 5 | –4 | |

| 82 | L3 | 1 | Lateral | 12 | 14 | –3 | |

| 8 | L4 | 1 | Lateral | 2 | 14 | –12 | x |

| 65 | L4 | 2 | Lateral | 5 | 16 | –11 | x |

| 69 | L4 | 1 | Lateral | 6 | 14 | –8 | |

| 72 | L4 | 1 | Lateral | 12 | 18 | –6 | |

| 28 | L4 | 1 | Medial | 12 | 12 | 1 | |

| 28 | L4 | 1 | Lateral | 4 | 27 | -23 | x |

| 47 | L4 | 1 | Lateral | 17 | 17 | 0 | |

| 49 | L4 | 2 | Lateral | 7 | 18 | –12 | x |

| 54 | L4 | 2 | Lateral | 8 | 15 | –8 | |

| 49 † | L4 | 3 | Lateral | 3 | 23 | –19 | x |

| 80 | L4 | 1 | Lateral | 15 | 15 | 0 | |

| 13 | L5 | 1 | Lateral | 15 | 22 | –6 | |

| 13 | L5 | 2 | Lateral | –3 | 29 | –32 | x |

| 17 | L5 | 1 | Medial | 10 | 17 | –7 | |

| 35 | L5 | 2 | Lateral | 3 | 17 | –14 | x |

| 46 | L5 | 1 | Lateral | 25 | 12 | 13 | x |

| 46 | L5 | 1 | Medial | 23 | 18 | 5 | |

| 54 | L5 | 1 | Lateral | 11 | 25 | –13 | x |

| 65 | L5 | 1 | Lateral | 12 | 32 | –20 | x |

| 77 | L5 | 1 | Lateral | 7 | 21 | –14 | x |

| 86 | L5 | 1 | Lateral | 10 | 10 | 0 | |

| 78 | S1 | 1 | Medial | 8 | 13 | –5 | |

*Pedicle fracture.

†Pedicle fracture + L4 radiculopathy postoperatively. |

Patient exposures in this study were low. The mean

maximum patient skin exposure for the last 5 cases was

44.9 mGy. The threshold for the lowest dose associated with deterministic radiation effects (early transient skin erythema)

is 2000 mGy,25 an order of magnitude higher than

our maximum skin dose.

Figure 5. Distribution of all screws with respect to vertebral level.

Both radiation exposure and length of procedure are shortened

with surgeon experience.26 With the exception of assisting

experienced surgeons or attending surgeon cadaver labs

to gain experience, the only alternative is to accept the inherent

learning curve with minimally invasive techniques such as

percutaneous pedicle screw placement. The senior surgeon’s

prospective database reveals a signifi cant reduction in operative

times from the initial 5 single-level percutaneous cases, at

an average of 238 minutes, to 147 minutes with the most recent

5 cases. The senior surgeon also limits exposure by standing 1 meter away from the radiation source whenever an x-ray

is taken where the surgeon does not need to directly handle

an instrument during fl uoroscopy. Although intraoperative

CT-guided percutaneous screw insertion is an alternative to

reduce surgeon radiation exposure, this has the dual disadvantage

of increasing patient exposure with an on-table CT

or additional preoperative CT, and reduced accuracy of screw

insertion.27

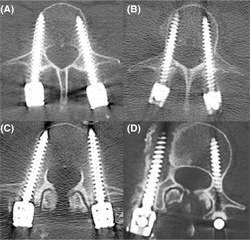

Figure 6. Axial CT images demonstrating grading of screw placement. (A) Grade 0. (B) Grade 1 ( < 2 mm cortical encroachment). (C) Grade 2: ( > 2 mm cortical encroachment). (D) Grade 3 (complication: pedicle fracture).

Figure 7. K-Wire complication. Care must be taken with K-wire insertion to ensure that the K-wire is not aggressively advanced into the vertebral body with puncture through the anterior aspect of the vertebra.

This clinical study has shown that percutaneous pedicle

screw insertion in the thoracolumbar spine under fl uoroscopic

guidance is a safe and reliable technique, with a

low misplacement rate and an extremely low rate of complications

compared with the high rates published in the

literature. The drawbacks to this technique include the

inherent learning curve, increased exposure to ionizing

radiation, and increased operating times compared to an

open surgical approach. Once the concepts and techniques

of this procedure have been mastered, however, it offers a

less traumatic, more aesthetic, and equally effective method

for posterolateral fusion.

Key Points

- Percutaneous insertion of cannulated pedicle screws

in the thoracic and lumbar spine is an acceptable

technique with a low complication rate in experienced

hands.

- Insertion of percutaneous pedicle screws is a technically

demanding technique with a steep learning

curve and should be performed with appropriate

training and attention to detail.

- Consistency in the method of screw grading is needed

for comparative studies. We introduce a simple grading

system (Mobbs Raley) for the CT-guided evaluation

of pedicle screw placement.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Marcus Cremonese, BA, RBI, AIMB

(E-mail: marcus@medicalillustration.com.au; Tel/Fax:

61 + 2 + 9365 5003) for medical illustration (Figures 1 A, B).

References

- France JC , Yaszemski MJ , Lauerman WC , et al. A randomized

prospective study of posterolateral lumbar fusion. Outcomes with

and without pedicle screw instrumentation . Spine (Phila Pa 1976)

1999 ; 24 : 553 – 60 .

- Foley KT , Gupta SK . Percutaneous pedicle screw fi xation of the

lumbar spine: preliminary clinical results . J Neurosurg 2002 ; 97

( 1 Suppl ): 7 – 12 .

- Perez-Cruet MJ , Foley KT , Isaacs RE , et al. Microendoscopic

lumbar discectomy: technical note . Neurosurgery 2002 ; 51

( 5 Suppl) : S129 – 36 .

- Khoo LT , Palmer S , Laich DT , et al. Minimally invasive percutaneous

posterior lumbar interbody fusion . Neurosurgery 2002 ; 51

( 5 Suppl ): S166 – 71 .

- Foley KT , Lefkowitz MA . Advances in minimally invasive spine

surgery . Clin Neurosurg 2002 ; 49 : 499 – 517 .

- Foley KT , Holly LT , Schwender JD . Minimally invasive lumbar

fusion . Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003 ; 28 ( 15 Suppl ): S26 – 35 .

- Castro WH , Halm H , Jerosch J , et al. Accuracy of pedicle

screw placement in lumbar vertebrae . Spine (Phila Pa 1976)

1996 ; 21 : 1320 – 4 .

- Farber GL , Place HM , Mazur RA , et al. Accuracy of pedicle screw

placement in lumbar fusions by plain radiographs and computed

tomography . Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995 ; 20 : 1494 – 9 .

- Gertzbein SD , Robbins SE . Accuracy of pedicular screw placement

in vivo . Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990 ; 15 : 11 – 4 .

- Belmont PJ Jr , Klemme WR , Dhawan A , et al. In vivo accuracy of

thoracic pedicle screws . Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001 ; 26 : 2340 – 6 .

- Odgers CJt , Vaccaro AR , Pollack ME , et al. Accuracy of pedicle

screw placement with the assistance of lateral plain radiography . J

Spinal Disord 1996 ; 9 : 334 – 8 .

- Sjostrom L , Jacobsson O , Karlstrom G , et al. CT analysis of pedicles

and screw tracts after implant removal in thoracolumbar fractures

. J Spinal Disord 1993 ; 6 : 225 – 31 .

- Wiesner L , Kothe R , Ruther W . Anatomic evaluation of two different

techniques for the percutaneous insertion of pedicle screws in

the lumbar spine . Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999 ; 24 : 1599 – 603 .

- Haaker RG , Eickhoff U , Schopphoff E , et al. Verifi cation of the

position of pedicle screws in lumbar spinal fusion . Eur Spine J

1997 ; 6 : 125 – 8 .

- Wiesner L , Kothe R , Schulitz KP , et al. Clinical evaluation and computed

tomography scan analysis of screw tracts after percutaneous

insertion of pedicle screws in the lumbar spine . Spine (Phila Pa

1976) 2000 ; 25 : 615 – 21 .

- Holly LT , Foley KT . Three-dimensional fl uoroscopy-guided percutaneous

thoracolumbar pedicle screw placement. Technical note . J

Neurosurg 2003 ; 99 ( 3 Suppl ): 324 – 9 .

- Schwender JD , Holly LT , Rouben DP , et al. Minimally invasive

transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility

and initial results . J Spinal Disord Tech 2005 ; 18 ( Suppl 6) : S1 – 6 .

- Schizas C , Michel J , Kosmopoulos V , et al. Computer tomography

assessment of pedicle screw insertion in percutaneous posterior

transpedicular stabilization . Eur Spine J 2007 ; 16 : 613 – 7 .

- Schulze CJ , Munzinger E , Weber U . Clinical relevance of accuracy of

pedicle screw placement. A computed tomographic-supported analysis

. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998 ; 23 : 2215 – 20 ; discussion 20 – 21 .

- Kim YJ , Lenke LG , Cheh G , et al. Evaluation of pedicle screw

placement in the deformed spine using intraoperative plain radiographs:

a comparison with computerized tomography . Spine (Phila

Pa 1976) 2005 ; 30 : 2084 – 8 .

- Ebraheim NA , Rollins JR Jr , Xu R , et al. Projection of the lumbar

pedicle and its morphometric analysis . Spine (Phila Pa 1976)

1996 ; 21 : 1296 – 300 .

- Gunzburg R , Gunzburg J , Wagner J , et al. Radiologic interpretation

of lumbar vertebral rotation . Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992 ; 16 : 660 – 4 .

- Bindal RK , Glaze S , Ognoskie M , Tunner V , Malone R , Ghosh

S . Surgeon and patient radiation exposure in minimally invasive

transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion . J Neurosurg Spine

2008 ; 9 : 570 – 3 .

- ARPANSA . Recommendations for Limiting Exposure to Ionizing

Radiation (1995) and National Standard for Limiting Occupational

Exposure to Ionizing Radiation (republished 2002) . National

Occupational Health and Safety Commission , 1995 . http://www.

arpansa.gov.au/pubs/rps/rps1.pdf . Accessed January 2011.

- Synowitz M , Kiwit J . Surgeon’s radiation exposure during percutaneous

vertebroplasty . J Neurosurg Spine 2006 ; 4 : 106 – 9 .

- Gonzalvo A , Fitt G , Liew S , et al. The learning curve of pedicle

screw placement: how many screws are enough ? Spine (Phila Pa

1976) . 2009 ; 34 : E761 – 5 .

- Mobbs RJ , Sivabalan P , Li J . Technique, challenges and indications for

percutaneous pedicle screw fi xation . J Clin Neurosci 2011 ; 18 : 741 – 9 .

CT Scan Analysis of Percutaneous Fusion CT Scan Analysis of Percutaneous Fusion

You will need the Adobe Reader to view and print the above documents.

|