|

Minimally invasive surgery compared to open spinal fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar spine pathologies

Ralph J. Mobbs a,b,c,*, Praveenan Sivabalan b,c, Jane Li b,c

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of New South Wales, High Street, Randwick, New South Wales, Australia

- Spine Unit, Prince of Wales Hospital, Barker Street, Randwick, New South Wales, Australia

- Neuro Spine Clinic, Suite 7a, Level 7 Prince of Wales Private Hospital, Barker Street, Randwick, New South Wales 2031, Australia

Abstract

This clinical study prospectively compares the results of open surgery to minimally invasive fusion for

degenerative lumbar spine pathologies. Eighty-two patients were studied (41 minimally invasive surgery

[MIS] spinal fusion, 41 open surgical equivalent) under a single surgeon (R. J. Mobbs). The two groups

were compared using the Oswestry Disability Index, the Short Form-12 version 1, the Visual Analogue

Scale score, the Patient Satisfaction Index, length of hospital stay, time to mobilise, postoperative medication

and complications. The MIS cohort was found to have significantly less postoperative pain, and to

have met the expectations of a significantly greater proportion of patients than conventional open surgery.

The patients who underwent the MIS approach also had significantly shorter length of stay, time

to mobilisation, lower opioid use and total complication rates. In our study MIS provided similar efficacy

to the conventional open technique, and proved to be superior with regard to patient satisfaction, length

of hospital stay, time to mobilise and complication rates.

©2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The safety of traditional open techniques for pedicle screw

placement for spinal fixation is well documented.1,2 However, conventional

open spine surgery has several limitations reported

including extensive blood loss, postoperative muscle pain and

infection risk. Paraspinal muscle dissection involved in open spine

surgery can cause muscular denervation, increased intramuscular

pressure, ischaemia, necrosis and revascularisation injury resulting

in muscle atrophy and scarring which is associated with prolonged

postoperative pain and disability.3–12 This approach-related morbidity

is then often associated with lengthy hospital stays and significant

costs.13 Spinal fusion utilising muscle dilating approaches

to minimise surgical incision length, surgical cavity size and the

amount of iatrogenic soft-tissue injury associated with surgical

spinal exposure, without compromising outcomes, is thus a desirable

advance.3–12

The current trend favours minimally invasive surgery (MIS) of

the spine due to lower complication rates and approach-related

morbidity with minimal soft tissue trauma, reduced intraoperative

blood loss and risk of transfusion, improved cosmesis, decreased

postoperative pain and narcotic usage, shorter hospital stays,

earlier mobilisation with faster return to work and thus reduced overall health care costs.1,4,6–9,13–18 However, to our knowledge

there is no quality published articles showing that MIS is superior

to open spinal surgery. The aim of this study was to directly compare

the effectiveness of MIS to conventional open spinal fusion, by

assessing clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Patients

A total of 82 patients was prospectively followed during 2006 to 2010: 41 patients who had undergone an MIS spinal fusion procedure as well as 41 patients who had received the open surgical equivalent under a single surgeon (R.J.M). Patients treated within the public hospital system were allocated to the open group and within the private system to the MIS group. All patients were operated on by the senior surgeon (R.J.M.) as part of the inclusion criteria. Of these, 37 patients who underwent MIS and 30 patients who underwent open surgery were available for follow-up. Data collected on all patients included: the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Short Form 12 (SF-12) version 1, the Visual Analogue Scale

(VAS) score and the Patient Satisfaction Index (PSI). Outcome data were collected at the final patient follow-up. Patients were included

if they: were aged 18–75 years; and had a degenerative pathology only. All patients complained of either back pain, radiculopathy, claudication or a combination of these three symptoms.

All patients had pain resistant to prolonged conservative therapy (at least six months).

Patient demographic data, preoperative ODI and VAS responses,and operative characteristics for these surgical approaches aresummarised in Table 1. The indications for surgery were isthmic and degenerative spondylolisthesis, degenerative scoliosis and degenerative disc disease with canal stenosis. These were confirmed by dynamic radiographs, CT scans and MRI. The average follow-up time following MIS procedures was approximately 11.5 months (range: 5.40–20.10 months) in comparison to 18.7 months (range: 8.07–40.00 months) for open procedures.

2.2. Surgical techniques

2.2.1. Minimally invasive technique

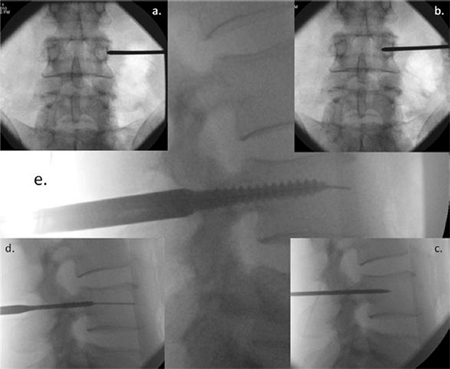

All percutaneous pedicle screws were inserted with the use of intraoperative radiographs (image intensifier [BV Endura], Philips

Electronics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). A radiolucent operative table (Jackson Spine Table, Orthopedic Systems, Union City, CA,

USA) was used. A posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) graft was inserted via a small (3–5 cm) midline incision over the disc

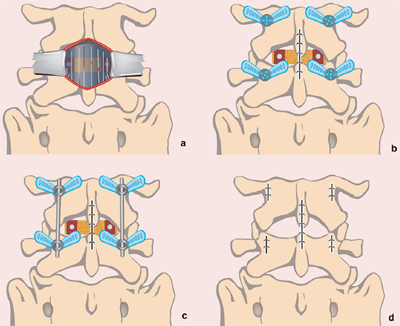

space to be fused (Fig. 1). A laminotomy was performed under microscopic visualisation, including a bilateral medial facetectomy to allow adequate decompression. The ligamentum flavum was then resected with rhizolysis of bilateral nerve roots. The intervertebral disc was then removed and the endplates prepared. Rotatable interbody cages filled with autologous bone, with or without synthetic bone, were placed into the evacuated disc space and were rotated for distraction. Any remaining bone graft was used to fill the remainder of the disc space (Fig. 1a). After achieving haemostasis and using copious antibiotic irrigation, the wound is closed in a routine fashion with 0 vicryl to the thoracolumbar fascia, 2-0 vicryl to the subcutaneous fat and 3-0 monocryl subcuticular sutures. Percutaneous pedicle screw–rod fixation was undertaken using

the Denali/Serengeti® system (K2M, Leesburg, VA, USA) or the minimal access non-traumatic insertion system (MANTIS ®) (Stryker,Kalamazoo, MI, USA). For a detailed review of the technique for percutaneous pedicle screw insertion, see19 (Figs. 2 and 3). Confirmation of pedicle screw placement is achieved with the image intensifier. The rods are then inserted via the pedicle screw incision sites and are joined to the pedicle screw heads. Tightening of the screw head caps allows for reduction of any spondylolisthesis (Fig. 1c). The MIS retractor sleeves are then removed, and all wounds are closed via the method described (Fig. 1d).

2.2.2. The conventional open technique

The conventional open technique involves a midline incision of

approximately 12 cm to 15 cm for a single level fusion, followed by

stripping and dissection of paraspinal muscles from the bilateral

laminae and facets. After exposure of the underlying bone, laminectomy

and bilateral facetectomy are performed. Discectomy

and distraction of the disc space using rotatable interbody cages

were performed with the same techniques and instruments as

the minimally invasive technique. Multiple systems were then utilised

for pedicle screw–rod fixation via the conventional technique

under direct visualisation within the same incision.

2.3. Assessment of results

Patient questionnaires were used to assess preoperative and

postoperative ODI, SF-1, VAS and PSI outcomes. The ODI was

scored according to the method of Mehra et al.20 The SF-12 was

scored according to the method outlined by Ware et al.21 The

VAS score was used to compare preoperative and postoperative

pain on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain) between the two

surgical groups. PSI was utilised to gauge postoperative patient

satisfaction with their corresponding procedure, where a score of

1 to 4 was provided (1 – surgery met my expectation, 2 – I did

not improve as much as I had hoped but I would undergo the same

operation for the same results, 3 – surgery helped but I would not

undergo the same operation for the same outcome, 4 – I am the

same or worse as compared to before surgery). Patients who had

inadequately completed, or who had failed to complete a particular

questionnaire were excluded from statistical analysis for that particular

questionnaire.

Clinical data such as age, gender, preoperative symptoms, preoperative diagnosis, surgical level and operation type, length of hospital

stay, time to mobilise, postoperative analgesia use, follow-up time and complications were analysed by viewing medical records. Length of stay was measured from the day of the operation (day 0) to the day of discharge. Time to mobilise was measured as the number of hours following admission to recovery until physiotherapy or nursing staff documented mobilisation of at least sit-to-stand. Along with medical records, patients were also requested to report any complications postoperatively as part of their questionnaires. Fusion was assessed by fine-cut coronal bone-window CT scans at the final follow-up visit. The assessment of fusion was made by two independent radiologists and not by the senior surgeon or his

research team.

Table 1

Demographic data for patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery (MIS) compared to open spinal fusion (open)

| - |

MIS |

Open |

p-value |

| No. patients (n) | 37 | 30 | |

| Age (years ± standard deviation) | 68.56 ± 12.99 | 67.48 ± 13.19 | 0.7379 |

| Gender (M/F) (% male) | 19/18 (51.35) | 16/14 (53.33) | 0.8717 |

| Follow-up time (months) | 11.46 ± 4.216 | 18.69 ± 8.129 | < 0.0001 |

| Preoperative diagnosis (no. [% of patients]) |

| Isthmic spondylolisthesis | 4 (10.81) | 9 (30.0) | 0.0650 |

| Degenerative spondylolisthesis | 18 (48.65) | 9 (30.0) | 0.1406 |

| Degenerative scoliosis | 1 (2.70) | 4 (13.33) | 0.1649 |

| Disc disease and canal stenosis | 14 (32.43) | 8 (26.67) | 0.7890 |

| Single level fusion (no. [% of patients]) | 29 (78.4) | 25 (83.3) | 0.6101 |

| T11/12 | 0(0) | 1 (3.3) | |

| L2/3 1 | (2.7) | 0 (0) | |

| L3/4 2 | (5.4) | 0 (0) | |

| L4/5 20 | (54.1) | 15 (50.0) | |

| L5/S1 6 | (16.2) | 9 (30.0) | |

| Multi-level fusion | 8 (21.6) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Preoperative ODI | 54.56% ± 19.47% (n = 34) | 52.38% ± 17.25% (n = 26) | 0.7825 |

| Preoperative VAS | 7.917 ± 1.505 (n = 36) | 8.259 ± 1.573 (n = 29) | 0.2113 |

F = female, L = lumbar, M = male, ODI = Oswestry Disability Index, S = sacral, T = thoracic, VAS = Visual Analogue Scale score.

R.J. Mobbs et al. / Journal of Clinical Neuroscience xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of a minimally invasive spinal fusion technique for a posterior lumbar interbody fusion: the ''80/20 technique'': (a) midline incision with the use of trimline retractor system to directly visualise the disc space for discectomy and insertion of rotatable interbody cages; (b) closure of midline incision and insertion of percutaneous pedicle screws; (c) insertion of rods joining ipsilateral pedicle screw heads; and (d) closure of wounds over pedicle screws. (This figure is available in colour at www.sciencedirect.com.)

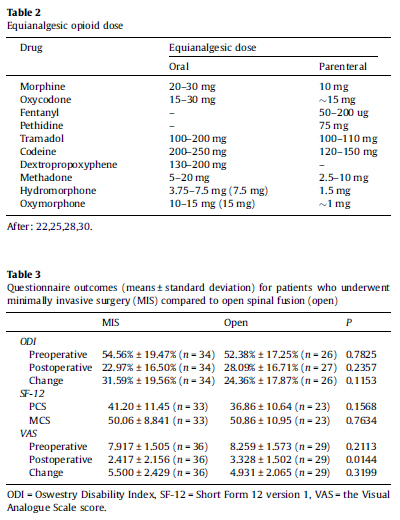

Postoperative analgesia in hospital until discharge was also analysed as an indirect measure of postoperative surgical pain, as pharmacological

agents are the cornerstone of acute postoperative pain management.22,23 Drugs used for postoperative pain include weak analgesia (paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAID]), opioids and adjuvants (antiepileptics, antidepressants).24 Pain medications that the patient was consuming prior to surgery for other conditions (for instance, arthritis) that were continued postoperatively during their hospital stay were included if they were opioids, NSAID or paracetamol as they would also contribute to treating postoperative pain. Potency refers to the power of a

medicinal agent to generate its desired outcome; thus, for analgesic medication, it is the dose required to produce a given analgesic effect.

22,25,26 In a similar fashion, equianalgesia refers to different doses of two agents that provide approximate pain relief.22 To our

knowledge, there is no quality literature directly comparing opioids, NSAID and paracetamol with regard to equianalgesia.24 To

analyse postoperative analgesia, the drugs administered were divided into two groups: opioid and non-opioid analgesia. Equianalgesic tables list opioid doses that produce approximately the same amount of analgesia based on bioavailability and potency.22,26–28 Table 2 illustrates the range of equianalgesic dose equivalents found in our literature search.22,25–32 To determine the total postoperative opioid utilisation by an individual patient, we converted each opioid the patient had consumed postoperatively to intravenous morphine equivalents using the

equianalgesic table provided. The less traumatic surgical approach involved with MIS techniques results in less postoperative pain

than conventional open techniques and is thus believed to potentially decrease postoperative narcotic use.11,13 Non-opioid analgesia

in this study refers to NSAID and paracetamol.33

2.4. Statistical analysis

Unpaired t-tests were utilised to compare normally distributed

continuous data. ODI (preoperative, change), VAS (preoperative

and postoperative), length of stay, time to mobilise, opioid and

non-opioid usage were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test.

The dichotomous variables (gender, surgical level) between the

two procedures were analysed using chi-squared analysis, whereas

preoperative diagnosis, PSI and complications were analysed using

Article in Press

R.J. Mobbs et al. / Journal of Clinical Neuroscience xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

Fig. 2. Image intensifier radiographs of the percutaneous screw insertion technique showing: (a) anterior/posterior (AP) view of the Jamshidi needle docked onto the lateral

aspect of the pedicle – the ''3 o'clock position''; (b) AP view of advancement of the needle 20 mm to 25 mm into the vertebral body; (c) lateral view, checking the position of

the Jamshidi needle; (d) lateral view, the K-wire and tapping of the pedicle; and (e) lateral view, insertion of the pedicle screw.

the Fisher exact test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

There was no statistical difference with respect to age, gender,

preoperative diagnosis, single compared to multiple surgical levels,

preoperative ODI and preoperative VAS scores between the two

surgical groups. ODI and VAS was significantly lower postoperatively

than ODI and VAS preoperatively among both the MIS and

open procedures (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference

between the MIS and open procedures for postoperative ODI, SF-

12 physical and mental component scores. However, the postoperative

VAS pain scores were significantly lower for the MIS cohort

than the open cohort (p = 0.0144; Table 3). A similar proportion

of MIS (83.3%) and open (78.6%) patients were satisfied undertaking

surgery for the benefit they received with their procedure (options

1 and 2). However, surgery met the expectations (option 1) of

a significantly greater proportion of patients who had undergone

MIS than the open procedure (p = 0.0236). The results for the PSI

are illustrated in Fig. 4 and Table 4.

The MIS technique resulted in a significantly shorter hospital

stay (p = 0.0016) and time to mobilise (p = 0.0021) after surgery

than the open technique. The MIS group had a significantly lower

postoperative usage of IV morphine (opioid) (85.90 mg) compared

to the open group (168.9 mg) (p = 0.0130). However, the usage of

non-opioids was not significantly different between the MIS and

open groups (Table 5).

The complications within both groups are depicted in Table 6.

There was a significantly lower complication rate utilising the

MIS compared to the conventional open technique (p = 0.0040). There were two cases of infection with the open technique in

comparison to one case utilising the MIS technique (urinary tract

infection – no wound infections). One patient in the MIS group

developed a painful haematoma postoperatively and presented

with sacral and bilateral leg numbness. Their motor function

remained intact. One patient in the open group also experienced

postoperative radiculopathy. The patient was observed without

treatment and the radiculopathy improved with time; however,

the patient experienced long-term sensory impairment. One

patient in the open cohort suffered a dural tear, with the patient

complaining of headaches and vomiting following the procedure,

which prolonged the length of stay. The patient was managed

Article in Press

R.J. Mobbs et al. / Journal of Clinical Neuroscience xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

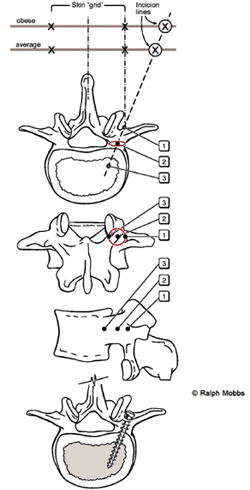

Fig. 3. Diagrams illustrating the anatomical principles of percutaneous pedicle

screw insertion: views from top to bottom: (a) superior; (b) posterior, (c) lateral, (d)

superior. First the initial skin incision is made with the patient's body habitus

considered. Second, the Jamshidi needle is first be ''docked'' onto the lateral aspect

of the pedicle – ''position 1'' – on the anterior/posterior image intensifier (II)

radiograph projection. Third, the Jamshidi needle is advanced 20 mm to 25 mm so

that the needle is beyond the medial border of the pedicle and into the vertebral

body – to ''position 3''. Finally, the position is confirmed by lateral II radiograph

projection before insertion of the K-wire.

with bed rest for eight to nine days with no long-term sequelae.

Two patients in the open group experienced non-union. This

was determined following complaints of worsening mechanical

lower back pain at the operation site over 9 to 12 months and

significant motion and subsidence on flexion–extension lateral

radiographs and CT scans. Subsequent revision surgery was

required for both patients. Three patients in the open group also

incurred paralytic ileus, determined by postoperative nausea and vomiting. One patient in the open cohort suffered deep vein

thrombosis.

Fig. 4. Graph of the outcomes of the Patient Satisfaction Index (PSI) showing that

most patients in both groups had clinically significant improvements; however,

those who underwent the minimally invasive spinal (MIS) fusion technique had a

greater proportion of patients in Group 1 than did patients from the Open group. PSI

outcomes: 1 – surgery met my expectation, 2 – I did not improve as much as I had

hoped but I would undergo the same operation for the same results, 3 – surgery

helped but I would not undergo the same operation for the same outcome, 4 – I am

the same or worse as compared to before surgery).

4. Discussion

Detachment and retraction of paraspinal muscle and the excessive

intraoperative dissection required for open procedures can result

in denervation, atrophy and irreversible muscle injury. MIS approaches attempt to achieve the goals of conventional open surgery

and solve the aforementioned problems by minimising the

amount of iatrogenic soft tissue injury, by utilising smaller surgical

incisions.6,8,10,13,14,16,17,34 MIS, however, includes the use of imaging

for navigation during pedicle screw placement. The use of

imaging prolongs operating times, while also increasing patient

and surgeon exposure to ionising radiation.3,35 Furthermore MIS

techniques have steep learning curves, requiring a different set of

cognitive, psychomotor and technical skills.6,9,14,18 It is recommended

that surgeons have adequate experience with open procedures

before attempting MIS methods.15 Most studies agree that

operative times for MIS (90–220 minutes) are significantly longer

than conventional open spinal fusion (142–203 minutes), but this

depends on surgeon experience.9,12,13,16,17,36 Intraoperative blood

loss in MIS is significantly lower than in conventional open

approaches.3,13,16,36,37

Table 4

Results of the Patient Satisfaction Index (PSI) questionnaire for patients who

underwent minimally invasive surgery (MIS) compared to open spinal fusion (open).

| Option no. |

MIS |

Open |

p |

| 1 |

21 |

8 |

0.0236 |

| 2 |

9 |

14 |

0.0650 |

| 3 |

5 |

5 |

0.7367 |

| 4 |

1 |

1 |

1.0000 |

| Total |

36 |

28 |

- |

MIS approaches to spinal fusion have not yet been shown to be superior in effectiveness to traditional open techniques. In our study the ODI and SF-12 questionnaires were utilised to analyse the impact of these surgical techniques on patient disability and quality of life (QoL), and the VAS score was used to assess pain. Both groups showed significant improvements in QoL and reduction in disability following surgery, with the ODI reduced from 54% to 22% for the MIS technique (p < 0.0001), and from 52% to 28% for the open technique (p < 0.0001). Significant reductions in

pain postoperatively were observed following each technique, with the VAS score being reduced from 7.9 to 2.4 for the MIS technique (p < 0.0001) and from 8.2 to 3.3 for the open technique (p < 0.0001).

Postoperative pain was significantly lower following the MIS technique (2.4 compared to 3.3), but despite this, the amount of pain relief (change in VAS score) provided by both procedures was not significantly different. Studies show that clinical outcomes such as pain and disability following spinal fusion improve for 12 months, with little further improvement or even

worsening after this point.38,39 Our results suggest MIS is just as effective as open spinal fusion, similar to other studies.3,40 However, a study by Kasis18 comparing PLIF procedures (standard compared to less-invasive) found significantly greater improvements for the less invasive PLIF group.18 Additionally, with regard to patient satisfaction, measured using the PSI, our results suggest that a significantly greater proportion of patients had their expectations met following the MIS technique (58%) than the open technique

(28%). These findings suggest that the MIS approach provides

greater patient satisfaction while being as effective, if not more

so, than the conventional open approach.

Reducing iatrogenic tissue injury during surgery should theoretically

reduce recovery time, time to mobilisation, and length

of stay in hospital.13,40 Our study found that the average length

of hospitalisation for the MIS group was 5.89 days (range:

2–20 days), which is significantly shorter than the 9.66 days

(range: 3–29 days) required by the open group. Furthermore the

average time to begin mobilisation following the MIS technique

was 21 hours (range: 12–51 hours), which was again significantly

shorter than the open technique, which required 31 hours (range:

12.5–70.5 hours). Similar results have been found in the literature

with average length of stay ranging from 2.24 days to 9.3 days

compared to 4 days to 10.8 days, and the average time to mobilise

ranging from 1.22 days to 3.2 days compared to 2.97 days to

5.4 days for minimally invasive and open techniques, respectively.

13,16–18,36,37,40 These results emphasise the clinical advantages

of MIS approaches with regard to recovery, which offset the

costs of specialised and expensive equipment, ultimately making

it a cheaper option than traditional open spinal fusion.37,40

Our study contradicts other studies on MIS techniques in that

the complication rate is lower in the MIS group, rather than the

open group. The explanation is most likely that the senior surgeon

performs a greater number of MIS operations than open procedures.

In addition, the senior surgeon has performed over 700 percutaneous

pedicle screw insertions and his accuracy is greater

using percutaneous techniques than open techniques.

The goal of postoperative pain management is to relieve pain

while keeping side effects to a minimum.23,24,41 The decreased

postoperative pain associated with MIS techniques potentially reduces

narcotic use, which in turn make the goals of postoperative

pain management more easily achievable.13,40 Our study showed a

statistically significant difference in opioid usage between the MIS

approach (85 mg) and the open approach (168 mg) suggesting that

MIS techniques reduce narcotic use along with their undesirable

side effects.

Table 5

Perioperative data for patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery (MIS) compared to open spinal fusion (open)

|

MIS |

Open |

p |

| Average length of hospital stay (±SD) [median] (days) |

5.889 ± 3.133 [5] (n = 36) |

9.655 ± 6.699 [8] (n = 29) |

0.0016 |

| Average time to mobilise (±SD) [median] (hours) |

21.86 ± 9.833 [18] (n = 36) |

31.24 ± 15.30 [24] (n = 29) |

0.0021 |

| Opioids (±SD) [median] (mg of IV morphine) |

85.90 ± 109.0 [46.67] (n = 37) |

168.9 ± 170.6 [103.8] (n = 26) |

0.0130 |

| Non-opioid analgesia (±SD) [median] (g of paracetamol) |

25.81 ± 12.44 [23.00] (n = 37) |

34.81 ± 25.17 [30.00] (n = 26) |

0.1176 |

| IV = intravenous, SD = standard deviation. |

Some of the common complications for spinal fusion procedures include hardware malpositioning, deep vein thrombosis, cerebrospinal fluid leak, paralytic ileus, damage to blood vessels and nerve roots, infections, pseudoarthrosis, neurological deficit, haematoma and cardiopulmonary complications.37,40 Complications with MIS techniques may be more difficult to assess and repair. 13,16,40 Some authors also believe that minimal exposure is also associated with incomplete treatment of pathology,14 especially considering that bleeding tendencies significantly increase the difficulty of MIS procedures by reducing visualisation.10 Studies have shown similar total complication rates for the MIS and open approaches. 13,16,40 However, in contrast to previous publications, the complication rate in our study for the MIS technique (5%), which is similar to that reported in the literature (0–19%), was significantly lower than the complication rate for the open technique (33%), which is slightly higher than reported in the literature (16–27%).40

4.1. Study limitations

Our current study has limitations including: small sample size, short follow-up time, results influenced by other conditions (for instance, arthritis) and other operations following spinal fusion.Limitations also exist in the method we utilised to compare postoperative analgesia. The equianalgesic doses are rough estimates and remain controversial.25 By comparing opioid and non-opioid usage separately31,41,42 our study neglects the synergistic effect of postoperative analgesia. As a way to overcome these limitations, long-term, randomised, prospective studies which use larger sample sizes with longer term follow-up are needed.

5. Conclusion

Spinal fusion remains the gold standard in maintaining the stability

of unstable spinal segments for multiple potential pathologies.

The MIS technique provides similar efficacy to the

conventional open technique, and proves to be superior in regards

to patient satisfaction, length of hospital stay, time to mobilise and

complication rates provided a good understanding of surgical anatomy

is present. As a result it is expected that MIS will become a

prominent part of spinal surgery and that indications for MIS fusion

will expand.

References

- Kanter AS, Mummaneni PV. Minimally invasive spine surgery. Neurosurg Focus

2008;25:E1.

- Mayer HM. A new microsurgical technique for minimally invasive anterior

lumbar interbody fusion. Spine 1997;22:691–9 [discussion 700].

- Harris EB, Massey P, Lawrence J, et al. Percutaneous techniques for minimally

invasive posterior lumbar fusion. Neurosurg Focus 2008;25:E12.

- Hsieh PC, Koski TR, Sciubba DM, et al. Maximizing the potential of minimally

invasive spine surgery in complex spinal disorders. Neurosurg Focus

2008;25:E19.

- Lipson SJ. Spinal-fusion surgery – advances and concerns. N Engl J Med

2004;350:643–4.

- Kan P, Schmidt MH. Minimally invasive thoracoscopic approach for anterior

decompression and stabilization of metastatic spine disease. Neurosurg Focus

2008;25:E8.

- Assaker R. Minimal access spinal technologies: state-of-the-art, indications, and

techniques. Joint Bone Spine 2004;71:459–69.

- Selznick LA, Shamji MF, Isaacs RE. Minimally invasive interbody fusion for

revision lumbar surgery: technical feasibility and safety. J Spinal Disord Tech

2009;22:207–13.

- Kerr SM, Tannoury C, White AP, et al. The role of minimally invasive surgery in

the lumbar spine. Oper Techn Orthop 2007;17:183–9.

- Beisse R. Endoscopic surgery on the thoracolumbar junction of the spine. Eur

Spine J 2006;15:687–704.

- Foley KT, Holly LT, Schwender JD. Minimally invasive lumbar fusion. Spine

2003;28:S26–35.

- Foley KT, Gupta SK. Percutaneous pedicle screw fixation of the lumbar spine:

preliminary clinical results. J Neurosurg 2002;97(1 Suppl.):7–12.

- Park Y, Ha JW. Comparison of one-level posterior lumbar interbody fusion

performed with a minimally invasive approach or a traditional open approach.

Spine 2007;32:537–43.

- Oppenheimer JH, DeCastro I, McDonnell DE. Minimally invasive spine

technology and minimally invasive spine surgery: a historical review.

Neurosurg Focus 2009;27:E9.

- Holly LT, Schwender JD, Rouben DP, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal

lumbar interbody fusion: indications, technique, and complications. Neurosurg

Focus 2006;20:E6.

- Shunwu F, Xing Z, Fengdong Z, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar

interbody fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar diseases. Spine

2010;35:1615–20.

- Ghahreman A, Ferch RD, Rao PJ, et al. Minimal access versus open posterior

lumbar interbody fusion in the treatment of spondylolisthesis. Neurosurgery

2010;66:296–304 [discussion].

- Kasis AG, Marshman LAG, Krishna M, et al. Significantly improved outcomes

with a less invasive posterior lumbar interbody fusion incorporating total

facetectomy. Spine 2009;34:572–7.

- Mobbs RJ, Sivabalan P, Li J. Technique, challenges and indications for

percutaneous pedicle screw fixation. J Clin Neurosci 2011;18:741–9.

- Mehra A, Baker D, Disney S, et al. Oswestry disability index scoring made easy.

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2008;90:497–9.

- Ware JE, Keller SD, Kosinski M. SF-12: how to score the SF-12 physical and mental

health summary scales. 2nd ed. Boston: The Health Institute, New England

Medical Center; 1995.

- Anderson R, Saiers JH, Abram S, et al. Accuracy in equianalgesic dosing.

Conversion dilemmas. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;21:397–406.

- Ramsay MA. Acute postoperative pain management. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc

2000;13:244–7.

- Rahman MH, Beattie J. Managing post-operative pain. Pharm J 2005;275:

145–8.

- Knotkova H, Fine PG, Portenoy RK. Opioid rotation: the science and the

limitations of the equianalgesic dose table. J Pain Symptom Manage

2009;38:426–39.

- Gordon DB, Stevenson KK, Griffie J, et al. Opioid equianalgesic calculations. J

Palliat Med 1999;2:209–18.

- Gammaitoni AR, Fine P, Alvarez N, et al. Clinical application of opioid

equianalgesic data. Clin J Pain 2003;19:286–97.

- Patanwala AE, Duby J, Waters D, et al. Opioid conversions in acute care. Ann

Pharmacother 2007;41:255–66.

- Doyle D, Hanks G, Cherny N, et al. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. Oxford

University Press; 2005.

- Wilder-Smith CH, Schimke J, Osterwalder B, et al. Oral tramadol, a l-opioid

agonist and monoamine reuptake-blocker, and morphine for strong cancerrelated

pain. Ann Oncol 1994;5:141–6.

- Krenzischek DA, Dunwoody CJ, Polomano RC, et al. Pharmacotherapy for

acute pain: implications for practice. J Perianesth Nurs 2008;23(Suppl. 1):

S28–42.

- Hughes J, Hughes W. Clinical pharmacy: a practical approach. Australia:

Macmillan Publishers; 2001.

- Derry S, Barden J, McQuay HJ, et al. Single dose oral celecoxib for acute

postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;CD004233.

- Smith JS, Ogden AT, Fessler RG. Minimally invasive posterior thoracic fusion.

Neurosurg Focus 2008;25:E9.

- Teitelbaum GP, Shaolian S, McDougall CG, et al. New percutaneously inserted

spinal fixation system. Spine 2004;29:703–9.

- Regan JJ, Yuan H, McAfee PC. Laparoscopic fusion of the lumbar spine:

minimally invasive spine surgery. A prospective multicenter study evaluating

open and laparoscopic lumbar fusion. Spine 1999;24:402–11.

- Wang MY, Cummock MD, Yu Y, et al. An analysis of the differences in the acute

hospitalization charges following minimally invasive versus open posterior

lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine 2010;12:694–9.

- Andersen T, Christensen FB, Niedermann B, et al. Impact of instrumentation in

lumbar spinal fusion in elderly patients. Acta Orthop 2009;80:445–50.

- Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, et al. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical

Studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain:

a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine

Study Group. Spine 2001;26:2521–32 [discussion 32-4].

- Villavicencio AT, Burneikiene S, Roeca CM, et al. Minimally invasive versus open

transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Surg Neurol Int 2010;1:12.

- Bonnet F, Marret E. Postoperative pain management and outcome after surgery.

Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2007;21:99–107.

- White PF, Kehlet H. Improving postoperative pain management: what are the

unresolved issues? Anesthesiology 2010;112:220–5.

Minimally Invasive Surgery compared to open Spinal Fusion Minimally Invasive Surgery compared to open Spinal Fusion

You will need the Adobe Reader to view and print the above documents.

|