|

Phrenic nerve stimulation: The Australian experience

Peter Khong a,*, Amanda Lazzaro b, Ralph Mobbs a

- Department of Neurosurgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Barker Street, Randwick, New South Wales 2031, Australia

- School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales Kensington Campus, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

Phrenic nerve stimulation is a technique whereby a nerve stimulator provides electrical stimulation of

the phrenic nerve to cause diaphragmatic contraction. The most common indications for this procedure

are central alveolar hypoventilation and high quadriplegia. This paper reviews the available data on the

19 patients treated with phrenic nerve stimulation in Australia to date. Of the 19 patients, 14 required

pacing due to quadriplegia, one had congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and one had brainstem

encephalitis. Information was unavailable for the remaining three patients. Currently, 11 of the pacers are

known to be actively implanted, with the total pacing duration ranging from 1 to 21 years (mean

13 years). Eight of the 19 patients had revision surgeries. Four of these were to replace the original I-

107 system (which had a 3–5-year life expectancy) with the current I-110 system, which is expected

to perform electrically for the patient's lifetime. Three patients had revisions due to mechanical failure.

The remaining patients' notes were incomplete. These data suggest that phrenic nerve stimulation can be

used instead of mechanical ventilators for long-term ongoing respiratory support.

© 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Phrenic nerve stimulation is a technique whereby a nerve stimulator provides electrical stimulation of the phrenic nerve to cause diaphragmatic contraction. First described conceptually by Duchenne1 in 1872 as the ''best means of imitating natural respiration", the groundbreaking work came in the late 1960s by Glenn et al.2–4 –subsequently, in conjunction with Avery Biomedical Devices (Commack,NY, USA), the first phrenic nerve stimulators were brought into commercial distribution. Phrenic nerve stimulation has been practiced for several decades in Australia, with the first being performed in 1977; however, it remains relatively uncommon.

The two main indications for phrenic nerve stimulation are central alveolar hypoventilation and high quadriplegia. Of the former,

children suffering from congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS) form a unique group that often benefit drastically from this procedure. In the latter, patients typically with high cervical injuries (at or above C3) are the best candidates. The ultimate aim is to improve quality of life through temporary or permanent relief from the use of an artificial ventilation device.

Although phrenic nerve stimulation has now been described, and practiced, for several decades, it is still in its relative infancy, and there is still much work in innovation and advancement in this area. We describe the Australian experience of phrenic nerve stimulation in this series. To date, there have only been 19 patients who have undergone this procedure in Australia (Table 1).

2. Methods and device

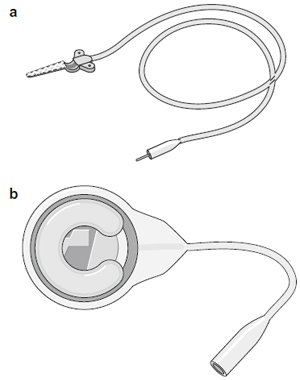

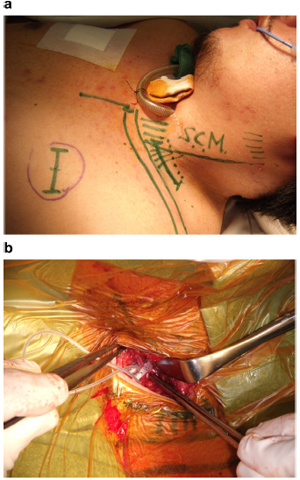

The phrenic nerve stimulator consists of an electrode placed on the phrenic nerve and connected to a subcutaneous receiver via lead wires (Fig. 1). An external battery-operated transmitter sends radiofrequency energy to the receiver through an antenna, which is placed on the skin overlying the receiver. The receiver converts this energy into an electrical current that is directed to the phrenic nerve in order to stimulate the nerve, thereby causing contraction of the diaphragm.

The surgery can be performed via either a cervical or thoracic approach.

2.1. Cervical approach

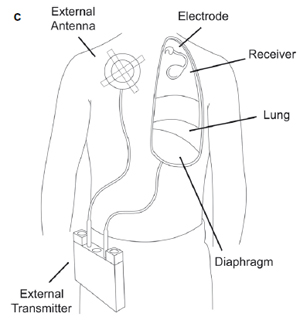

A linear, horizontal skin incision is made and the sternocleidomastoid muscle is retracted medially. The phrenic nerve is identified

over the anterior scalenus muscle and isolated, and an electrode is attached (Fig. 2). The lead is tunnelled into a pocket in the anterior chest wall, and the receiver placed in a subcutaneous pocket.

2.2. Thoracic approach

This procedure is performed either via open thoracotomy at the 2nd or 3rd intercostal space, or thorascopically using trochars at

the 5th, 7th and 9th intercostal spaces along the posterior axillary line. The lungs are deflated one side at a time and the phrenic nerve

is mobilised over cardiac structures. The electrode is positioned

P. Khong et al. / Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 17 (2010) 205–208

Table 1

Details of the 19 patients with phrenic nerve stimulators implanted in Australia

| Patient |

Age (yrs),

sex |

Diagnosis |

Pacer status

(no. yrs) |

Location |

Reason for reoperation |

| 1 |

U, M |

Not on file |

? Active: Implanted |

Not on file |

N/A |

| 2 |

U, F |

Not on file |

Deceased: Unknown |

C unilateral (R) |

N/A |

| 3* |

35, F |

Quadriplegia |

Deceased: Implanted |

T bilateral |

Upgrade 5 yrs after initial surgery§ |

| 4 |

47, M |

Complete tetraplegia: C4–5 fracture

with ascending paralysis to C2–3 level |

Deceased: Implanted |

C unilateral (L) |

N/A |

| 5* |

30, F |

Quadriplegia |

Active: Implanted (21) |

C bilateral |

Upgrade 5 yrs after initial surgery§ |

| 6* |

28, M |

Quadriplegia |

Active: Implanted (21) |

T bilateral |

Upgrade 5 yrs after initial surgery§ |

| 7* |

38, F |

Quaplegia: C3–4 incomplete

quadriplegia |

Deceased: Unknown |

Not on file |

Upgrade 5 yrs after initial surgery§ |

| 8 |

63, F |

Quadriplegia: C1–2 fracture,

complete C2 quadriplegia |

Deceased: Unknown |

C bilateral |

N/A |

| 9* |

38, M |

Quadriplegia |

Active: Implanted (17) |

C bilateral |

Malfunction in pacer 4 yrs after initial surgery, upgraded§ |

| 10** |

19, F |

Quadriplegia: High cervical quadriplegia,

disrupted spinal cord at C1–2 level |

Active: Implanted (15) |

T bilateral |

Failure of both right and left receivers due to breast

development; receivers replaced in a more

inferior and superficial position |

| 11 |

66, F |

Not on file |

Deceased: Unknown |

T bilateral |

N/A |

| 12* |

15, M |

CCHS |

Deceased: Unknown |

T bilateral |

Not on file |

| 13 |

36, F |

Quadriplegia |

Active: Implanted (12) |

C bilateral |

N/A |

| 14* |

15, M |

Brainstem encephalitis |

Active: Implanted (12) |

C bilateral |

R lead replacement due to mechanical failure |

| 15 |

16, M |

Quadriplegia |

Active: Implanted (12) |

C bilateral |

N/A |

| 16 |

33, F |

Quadriplegia |

Active: Implanted (11) |

C bilateral |

N/A |

| 17 |

28, M |

Quadriplegia |

Active: Implanted (10) |

T bilateral |

N/A |

| 18 |

7, F |

Quadriplegia: Pneumococcal mastoiditis

complicated by cervicomedullary infarct |

Active: Implanted (3) |

C bilateral |

N/A |

| 19 |

24, M |

Quadriplegia |

Active: Implanted (1) |

C bilateral |

N/A |

C = cervical, CCHS = congenital central hypoventilation syndrome, F = female, L = left, M = male, N/A = not available, R = right, T = thoracic, U = age unknown, yrs = years.

* = reoperation.

** = reoperation twice.

§ = upgrade from I-107 to I-110 system.

below the nerve and sutured into place. The leads are brought

through the thoracic cavity and tunnelled into a subcutaneous

pocket inferior to the 12th rib, and the receiver is placed into this

pocket.

Generally, pacing is initiated four to six weeks post-operatively,

and gradually increased over several weeks.

2.3. Methods of analysis

We reviewed the available data on patients who have had phrenic

nerve stimulators implanted in Australia. These data were obtained

from Avery Biomedical Devices, who have been, and are

currently, the sole distributor of this device to Australia. The available

medical records were then obtained from the relevant hospitals

and any additional useful information was retrieved from

these, including infections, failure of device, lead migration and

longevity of stimulation.

3. Results

A total of 19 patients have had phrenic nerve simulators implanted

in Australia. The first of these was performed in 1977;

however, this patient has been lost to follow-up. Seven of the 19

patients have since died. Unfortunately the information regarding

cause of death was unavailable in all but one patient, who died

from pneumonia.

Eleven patients are still actively implanted, with total pacing

duration ranging from 1 year to 21 years. The average pacing duration

for actively pacing patients in whom records were available is

13 years. Several of the patients were either lost to follow-up or the

records were unobtainable.

In the 16 patients on whom information was available regarding

the original condition that required the use of phrenic nerve

stimulators, 14 were listed as having quadriplegia (most were traumatic,

although one was related to a cervicomedullary infarct following

pneumococcal mastoiditis), one patient suffered from

absent respiratory drive as a result of brainstem encephalitis, and

one patient had CCHS.

Eleven patients underwent cervical approaches, of which two

were unilateral and nine were bilateral. Six patients had thoracic

approaches, all of which were bilateral. There were two undocumented

approaches.

Eight patients had repeat operations for replacement/reimplantation

of hardware. The original I-107 receiver design was known

to have a 3-year to 5-year life expectancy, and four patients have

had re-implantations for this reason. The current I-110 receiver design

is expected to perform electrically for the patient's lifetime.

Of the reasons for the other replacement/reimplantations, one

patient's notes were not on file, and the other three were all related

to mechanical failure.

One patient experienced malfunction of the diaphragmatic

pacemaker 4 years after initial surgery, requiring ventilation at

home. Eventually, a I-110 pacer was used to replace the older I-

107 device. One patient required lead replacement on the right

side due to mechanical failure of implanted components – in the

interim, he required full ventilation during sleep for 1 month.

Another patient experienced failure of both left-sided and then

right-sided receivers due to breast development. The receivers

were replaced in a more inferior and superficial position (with ventilation

via tracheostomy used in the interim). In a recent followup

of this patient 15 years after the initial surgery, she was using

the pacing during the day and mechanical ventilation at night.

The left pacer was also noted to be less efficient – this was due

to difficulty in locating the antenna over the receiver due to weight

gain, and increasing the amplitude of the stimulating current of the

transmitter provided some improvement to this problem.

Of the patients on whom follow-up information was readily obtained,

several complications were noted in most. These were not unexpected, and typical of patients with quadriplegia. They included

recurrent respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections,

pressure sores, kyphoscoliosis, neurogenic bladder and

muscle spasms.

P. Khong et al. / Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 17 (2010) 205–208

Fig. 1. The phrenic nerve stimulator system showing (a) a monopolar electrode, (b)

a I-110 receiver (Avery Biomedical Devices; Commack, NY, USA) and (c) location of

the system components.

Fig. 2. (a) Surface marks on a patient indicating position of the incision (dotted line) in relation to the clavicle, sternocleidomastoid (S.C.M.), and the position of the subcutaneous receiver (broken circle). (b) Intraoperative photograph showing attachment of the electrode to the phrenic nerve via the cervical approach. This figure is available in colour at www.sciencedirect.com.

4. Discussion

Phrenic nerve stimulators can be implanted via two routes – a

cervical approach, or a thoracic approach. Initially, the thoracic approach

involved a thoracotomy, but more recently a less-invasive

thorascopic approach5 has been used successfully. Intramuscular

diaphragm stimulation is another technique described that aims

to cause less potential injury to the phrenic nerve through direct

stimulation of the diaphragm – however, electrode wires that exit

the skin carry a small but significant infection risk.6

Multiple complications may be associated with the implantation

of phrenic nerve stimulators. Complications involving the

hardware include mechanical failure, electrode failure or dislodgement,

and broken or disconnected wires – this can often result in

the replacement of the stimulator or reversion back to ventilatory

support. Lung complications including atelectasis, pneumonia and

pneumothorax are all possible with the thoracic approach.5 Infection

is also a potentially serious complication which may require

removal of the affected device. Damage to the phrenic nerve may

occur acutely during surgery and render a phrenic nerve stimulator

ineffective – there are also questions as to whether chronic, long term stimulation itself may damage the nerve over time or even

cause diaphragmatic failure, athough results thus far have been

positive and there is no evidence to support this.

Weese-Mayer et al.7 published a review of the international

experience with quadruple diaphragm pacer systems, which included

35 children and 29 adults. They noted that 2.9% of patients

experienced infection, and 3.8% experienced mechanical trauma.

Presumed electrode and receiver failure occurred in 3.1% and

5.9% of patients with tetraplegia and CCHS respectively. Overall,

the figures were overwhelmingly positive, with 94% of paediatric

patients pacing successfully, 60% of these complication free, and

86% of adult patients pacing successfully, 52% of these complication

free.

Garrido-Garcia et al.8 published a series in 1998 on 22 patients

treated with diaphragmatic stimulators: 18 patients achieved permanent

pacing, and the remaining four required pacing only during

sleep. One patient had phrenic nerve entrapment by scar

tissue and four experienced infections, all of whom required operative

reimplantation. Pacemaker complications included antenna

fractures and receiver failure. Five patients died during followup.

Although the mean duration of follow-up was only 3 to

4 months, one patient was followed up for 11 years and four for

10 years, indicating that it may be possible for diaphragmatic pacing

to achieve complete stable long-term ventilation.

Shaul et al.5 successfully implanted phrenic nerve stimulators

through a thoracoscopic approach. Nine patients, all children, were

described. Over a mean follow-up period of 30 months, eight patients

reached their long-term pacing goals. Four patients experienced

post-operative complications (pneumonia, atelectasis,

bradycardia and pneumothorax), with the recognition that aggressive

post-operative pulmonary hygiene was required.

Elefteriades et al.9 published long-term pacing results on 12 patients

with quadriplegia: six of 12 patients continued full-time

pacing with a mean of 14.8 years. Patients who stopped full-time

pacing did so due to social/financial reasons or medical comorbidities

rather than complications directly related to the phrenic nerve

stimulators themselves. They also pointed out that there was no

evidence to suggest long-term nerve injury could result from

chronic pacing, with no apparent clinical deterioration in pacing

parameters or respiratory measurements from continuous pacing

for over 10 to 15 years.

B. M. Soni, in his article "Use of phrenic nerve stimulator in high

ventilator dependent spinal cord injury" (P. Khong, pers. comm..

2009) reviewed 20 ventilator-dependent patients with high cervical

spinal cord injuries who had undergone phrenic nerve stimulator

implantation. One paediatric patient failed to produce adequate

tidal volumes with stimulation; one patient developed a cable fracture

requiring conversion of the system to an intrathoracic stimulator,

and 18 of the 20 patients reported significant benefit in

mobility, access and overall improvement in quality of life.

More recently, Hirschfeld et al.10 conducted a prospective study

comparing the outcomes of 64 spinal cord-injured patients who

were respiratory device-dependent. Half had functioning phrenic

nerves and diaphragm muscles and were treated with phrenic

nerve stimulators, and the other half with destroyed phrenic nerves were mechanically ventilated. They found that those treated

with phrenic nerve stimulators had a reduced frequency of

respiratory tract infections and improved quality of speech – these

results were statistically significant. Subjectively, they felt that

those with stimulators had improved quality of life.

In our case series, we found a total of 19 patients in whom phrenic

nerve stimulators have been implanted in Australia: 11 patients

had undergone cervical approaches and six had thoracic

approaches – this largely reflected surgeon preference, and to date

there are no conclusive data to show whether one approach is better

than another. Of interest, eight patients had to undergo reimplantations

– four were expected due to the 3-year to 5-year life

expectancy of the original I-107 receiver design, three were due

to mechanical failure (one patient's notes were not available).

5. Conclusion

To the time of writing, 19 patients have had phrenic nerve stimulators

implanted in Australia. Although the devices have been

available for several decades, their use is still regarded as specialised

and uncommon, especially in Australia. We acknowledge that

complications can arise attributable to mechanical failure, as well

as the expected complications inherent in patients with quadriplegia.

Of the patients known to be actively pacing, the average duration

of ongoing pacing is 13 years – this suggests that phrenic

nerve stimulators can be used in the long term instead of mechanical

ventilators for ongoing respiratory support. Follow-up studies

will be valuable in determining whether phrenic nerve stimulators

can be a permanent solution to the respiratory issues related to

central alveolar hypoventilation and high quadriplegia.

References

- Duchenne GB. De l'electrisation localisee et de son application a la pathologie et la

therapeutique par courants induits at par courants galavaniques interrompus et

conius. 3rd ed. Paris: J.B. Bailliere et Fils; 1872. pp 907–18.

- Judson JP, Glenn WWL. Radio-requency electrophrenic respiration. Long-term

application to a patient with primary hypoventilation. JAMA 1968;203:1033–7.

- Glenn WWL, Phelps ML, Elefteriades JA, et al. Twenty years of experience in

phrenic nerve stimulation to pace the diaphragm. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol

1986;9:780–4.

- Glenn W, Brouillett R, Dentz B, et al. Fundamental considerations in pacing of

the diaphragm for chronic ventilatory insufficiency; a multicentre study. Pacing

Clin Electrophysiol 1988;11:2121–7.

- Shaul DB, Danielson PD, McComb JG, et al. Thoracoscopic placement of phrenic

nerve electrodes for diaphragmatic pacing in children. J Pedriatr Surg

2002;37:974–8.

- DiMarco AF, Onders RP, Ignagni A, et al. Phrenic nerve pacing via intramuscular

diaphragm electodes in tetraplegic subjects. Chest 2005;127:671–8.

- Weese-Mayer DE, Silvestri JM, Kenny AS, et al. Diaphragm pacing with a

quadripolar phrenic nerve electrode; an international study. Pacing Clin

Electrophysiol 1996;19:1311–9.

- Garrido-Garcia H, Alvarcz JM, Escribano PM, et al. Treatment of chronic

ventilatory failure using a diaphragmatic pacemaker. Spinal Cord 1998;36:

310–4.

- Elefteriades JA, Quin JA, Hogan JF, et al. Long-term follow-up of pacing of the

conditioned diaphragm in quadriplegia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2002;25:

897–906.

- Hirschfeld S, Exner G, Luukkaala T, et al. Mechanical ventilation or phrenic

nerve stimulation for treatment of spinal cord injury-induced respiratory

insufficiency. Spinal Cord 2008;46:738–42.

Phrenic Nerve Stimulation Phrenic Nerve Stimulation

You will need the Adobe Reader to view and print the above documents.

|