|

Reconstruction versus no reconstruction of iliac crest defects following harvest for spinal fusion: a systematic review

A review

Anthony M. T. Chau, M.B.B.S. (Hons.),1 Lileane L. Xu,2 Rhys van der Rijt, M.B.B.S.,3

Johnny H. Y. Wong, M.B.B.S. (Hons.), M.Med.,1,4 Cristian Gra gnaniell o, M.D.,4

Ral ph E. Stanford, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., F.R.A.C.S.,2,5

and Ral ph J. Mobbs , M.B.B.S., M.S., F.R.A.C.S.2,6

1Department of Neurosurgery, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital; 2Faculty of Medicine, University of New South

Wales; 3Department of Neurosurgery, St. Vincent's Hospital; 4Department of Neurosurgery, Australian School

of Advanced Medicine, Macquarie University Hospital; 5Department of Orthopaedics, Prince of Wales

Hospital; and 6Department of Neurosurgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney, Australia

Object: Autologous bone from the iliac crest is commonly used for spinal fusion. However, its use is associated

with significant donor site morbidity, especially pain. Reconstructive procedures of the iatrogenic defect have been

investigated as a technique to alleviate these symptoms. The goal of this study was to assess the effects of reconstruction

versus no reconstruction following iliac crest harvest in adults undergoing spine surgery.

Methods: The authors searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2011,

Issue 4); MEDLINE (1948–Oct 2011); EMBASE (1947–Oct 2011); and the reference lists of articles. Randomized

controlled trials (RCTs) or nonrandomized controlled trials (NRCTs) were included in the study. Two independent

reviewers selected the studies, extracted data using a standardized collection form, and assessed for risk of bias.

Results: Three RCTs (96 patients) and 2 NRCTs (82 patients) were included. These had a moderate to high risk

of bias. The results suggest that iliac crest reconstruction may be useful in reducing postoperative pain, minimizing

functional disability, and improving cosmesis. No pattern of other clinical, radiological, or resource outcomes was

identified.

Conclusions: Although the available evidence is suboptimal, this systematic review supports the notion that iliac

crest reconstruction following harvest for spinal fusion may reduce postoperative pain, minimize functional disability,

and improve cosmesis.

(http://thejns.org/doi/abs/10.3171/2012.3.SPINE11979)

Key Words :: systematic review :: reconstructive surgery :: bone substitute

bone transplantation :: ilium :: postoperative complication :: spinal fusion

Abbreviations used in this paper: CHA = coralline hydroxyapatite;

ICM = inductive conductive matrix; NRCT = nonrandomized

controlled trial; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SF-36 = 36-Item

Short Form Health Survey; VAS = visual analog scale.

Autologous bone from the iliac crest has for decades

been harvested as a substrate for spinal

arthrodesis. Unfortunately, donor site morbidity

and the requirement for a second surgical site have been

major detriments for its unhindered use.6 Whereas most

donor site complaints usually resolve with time, a number

of patients unfortunately experience persisting symptoms

that become a significant source of postoperative morbidity.

Chronic pain at the iliac crest is arguably the most significant

complication, occurring in approximately 20% of

patients.20,26,28 The mechanism of the pain is unclear, but

has been speculated to be due to trauma to the periosteum

or muscle or to neuroma formation.32 Additionally, others have suggested that patients undergoing lumbar surgery

may have confusing, referred pain.9,18 A wide range of

other complaints, including quality of life and cosmetic

issues, have also been documented.20,26,28

Despite this, autograft from the iliac crest remains

the gold standard substrate because currently no substitute

supersedes its combined osteogenic, osteoinductive,

and osteoconductive potential in promoting bony fusion.6

For many surgeons, especially those in countries where

cost is an additional significant constraint, autograft remains

a reliable, attractive, and easily accessible option,

and so its utility remains widespread.4 Autograft from

other sites, notably local decompressed bone, has also become

widely used. In certain procedures, such as singlelevel

posterolateral lumbar fusion, local bone has been

shown to be equivalent to iliac crest harvest, although its

success decreases with increasing levels.27

While research into bone graft substitutes such as efforts have concurrently been made to support iliac crest autograft procedures by developing methods to alleviate donor site morbidity. Medical therapies that have been investigated include intraoperative31 and continuous

postoperative anesthetic administration,22,29 which have achieved mixed results.

Surgically, many techniques such as rounding of

bony edges,30 harvesting from the posterior instead of the

anterior iliac crest,2 and minimally invasive procedures,

among others, have been suggested.24 Finally, reconstruction

of the iatrogenic defect, first proposed by Hardy in

1977,14 has been investigated. Similar to the unknown

mechanism of donor site pain, the way in which reconstruction

may alleviate morbidity is also unclear.32

Currently, no systematic synthesis of the efficacy of this "backfill" procedure exists in the literature. Hence, the aim of this review is to assess the effects of reconstruction versus no reconstruction of iliac crest harvest defects in adult humans undergoing spine surgery.

Methods

Types of Studies

All prospective controlled human clinical studies

(level III-2 evidence or higher) were considered (see Table

1 for hierarchy of evidence). This included a search for

NRCTs as well as RCTs, in anticipation of a low number

of the latter.

Types of Participants

We considered male and female adult patients who

underwent

iliac crest harvest as a donor site for spinal surgery.

Types of Interventions

We compared the intervention of iliac crest reconstruction

versus no reconstructive procedure following

iliac crest harvesting. We considered all types of reconstructive

material, including autologous, allogeneic, and

synthetic materials.

Outcomes Assessed

The primary outcome assessed was the effect on

donor site pain. Secondary outcomes included quality

of life/functional disability, cosmetic appearance, radiological

analysis, resource use (such as hospital stay), and

any notable complications (such as skin necrosis, bursitis,

meralgia paresthetica, herniation, and gait disturbance).

Search Strategy

A literature search of the Cochrane Central Register

of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue

4); MEDLINE (via Ovid) (1948–Oct 2011); and EMBASE

(Ovid) (1947–Oct 2011) was performed in Week 3, October

2011. The specific prospective search protocol for

each database is outlined in Table 2. No language restrictions

were used. In addition, the reference lists and citation

history of all full-text articles retrieved were checked

using Scopus. A search for ongoing or recently completed

trials was performed in Week 1, November 2011 in the US Clinical Trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov), UK Current

Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com), and Australian

New Zealand Clinical Trials (www.anzctr.org.au)

registries by using similar keywords.

All titles were assessed, and where the abstract suggested

a potentially eligible study, the full text was retrieved.

Studies were critically evaluated for design and

risk of bias, and were classified according to level of evidence

(Table 1).23 Data were extracted onto a standardized

collection form by 2 independently working authors

(A.C. and L.X.) and entered into RevMan version 5.1.4.

TABLE 1: National Health and Medical Research Council hierarchy of evidence

| Level |

Study Design |

| I |

systematic review of level II studies |

| II |

RCT |

| III-1 |

pseudo-RCT |

| III-2 |

comparative study w/ concurrent controls |

| III-3 |

comparative study w/o concurrent controls |

| IV |

case series |

Results

Evidence Base

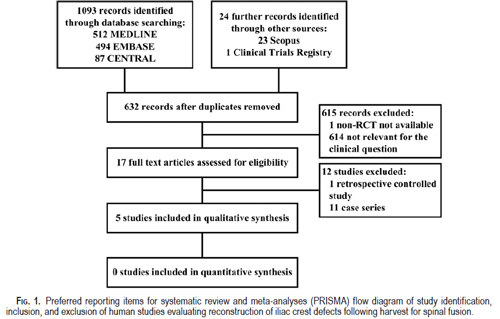

Included Studies: The literature search returned the following number of articles: CENTRAL (87), MEDLINE (512), and EMBASE (494) (Fig. 1). From these, 5 articles were found to be appropriate for the clinical question, of which 3 were RCTs5,25,33 and 2 were NRCTs

(Table 3).4,12 The indications for iliac crest harvesting in these studies were all related to spinal fusion. No studies from other disciplines such as oral maxillofacial surgery were located. The study by Yang et al.33 was translated into English and evaluated.

Excluded Studies: The search strategy yielded 1 controlled study, which was excluded because it was retrospective.32 A number of other studies were excluded due to their retrospective nature and/or lack of controls. 1,3,7,8,11,13–15,17,19,21 At the time of this writing, 1 prospective

NRCT had recently completed recruitment and was not yet available for analysis (see http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00837473).

Critical Appraisal of Included RCTs: Descriptions of

each included RCT are provided in Tables 4–6. The risk

of bias was assessed according to the guidelines set out in

the Cochrane Handbook (Table 7).16

Critical Appraisal of Included NRCTs: Descriptions

of the NRCTs are provided in Tables 8 and 9. The risk

of bias was assessed according to the validated checklist

developed by Downs and Black (Table 10).10

Statistical Analysis

Given the small number of patients from RCTs and

the heterogeneous interventions, a meta-analysis of data

was not performed.

TABLE 2: Literature search strategy, using MeSH (CENTRAL, MEDLINE) and Emtree (EMBASE) terms*

| No. |

CENTRAL |

MEDLINE |

EMBASE |

| 1 |

MeSH descriptor reconstructive surgical procedures

explode |

exp reconstructive surgical procedures |

exp plastic surgery |

| 2 |

MeSH descriptor bone transplantation explode all

trees |

exp bone transplantation |

exp bone transplantation |

| 3 |

MeSH descriptor bone substitutes explode all trees |

exp bone substitutes |

exp bone prosthesis |

| 4 |

MeSH descriptor prostheses and implants explode |

prostheses and implants.mp |

prostheses and implants.mp |

| 5 |

#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 |

or/1-4 |

or/1-4 |

| 6 |

MeSH descriptor ilium explode |

exp ilium |

exp iliac bone |

| 7 |

#5 AND #6 |

(iliac adj1 crest).mp. |

(iliac adj1 crest).mp. |

| 8 |

|

or/6-7 |

or/6-7 |

| 9 |

|

5 and 8 |

5 and 8 |

| 10 |

|

exp clinical trial |

clinical trial |

| 11 |

|

comparative study |

exp comparative study |

| 12 |

|

exp prospective studies |

exp prospective studies |

| 13 |

|

or/10-12 |

or/10-12 |

| 14 |

|

9 and 13 |

9 and 13 |

| 15 |

|

exp animals/ not humans.sh |

exp animals/ not humans.sh |

| 16 |

|

14 not 15 |

14 not 15 |

* adj1 = adjacent within 1 word; exp = explode search; mp = multiple posting (search term considered in the title, abstract, or

subject heading); sh = subject heading.

Surgical Technique

Anterior Harvest. Yang et al.33 harvested tricortical

bone from the anterior superior iliac spine, approximately

3.5–6 cm deep and 2.5–3 cm in thickness, by using an oscillating

saw and osteotome. The control group received bone wax for hemostasis. The reconstruction group received

selected autologous rib segments with the most appropriate

contour, followed by bone wax. The reasons for

harvest were anterior thoracic or lumbar fusion.

TABLE 3: Summary of included studies*

| Authors & Year |

Country |

Study Design |

Evidence Class |

Intervention |

Source |

| Yang et al., 2009 |

China |

RCT |

II |

autograft rib |

CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE |

| Bojescul et al., 2005 |

US |

RCT |

II |

CHA† |

CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE |

| Resnick, 2005 |

US |

RCT |

II |

β-TCP |

CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE |

| Bapat et al., 2008 |

India |

NRCT |

III-2 |

autograft rib |

MEDLINE, EMBASE |

| Epstein & Hollingsworth, 2003 |

US |

NRCT |

III-2 |

mesh & ICM |

CENTRAL, MEDLINE |

* β-TCP = beta–tricalcium phosphate.

† Pro Osteon 500 in this study.

Resnick25 harvested varying required amounts of tricortical

bone 2–4 cm lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine, 12–16 mm deep. Irrigation with antibiotics and saline

followed by cautery for hemostasis was applied. The

control group received Gelfoam hemostatic agent, whereas

the investigative group received packed morcellized

tricalcium phosphate. The reasons for harvest were 1- or

2-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, or 1-level

cervical corpectomy.

Bapat et al.4 harvested varying required amounts of

tricortical bone 3 cm posterior to the anterior superior

iliac spine. Sharp cortical edges were rounded off. Irrigation

and hemostasis were applied. In the investigative

group, 5-mm notches were prepared on either side of the

defect. A section of rib with the most appropriate contour

was then chosen, excised, and implanted into the iliac defect with impaction into the notches. The reasons for harvest

varied between groups, and are outlined in Table 8.

Epstein and Hollingsworth12 harvested an average

of 3-cm-long strut grafts from the left anterior iliac crest

by using an oscillating saw and curved osteotome (N.

E. Epstein, personal communication, 2012). The first 23

patients had bone wax applied to the cancellous surface.

The next 23 patients received iliac crest reconstruction in

which a MacroPore polymer sheet (MacroPore, Inc.) and

ICM (Sofamor Danek), a form of demineralized bone matrix

with minute amounts of bone morphogenetic protein

suspended in gel, were used. The ICM gel was warmed

and applied into the iliac crest defect, followed by application

of the contoured MacroPore sheet. Two resorbable

screws were placed on either side of the cortical shelves.

The reasons for harvest were for single-level anterior cervical

corpectomy and fusion.

TABLE 4: Characteristics of Yang study*

| Characteristic |

Data |

| methods |

RCT; duration 1 yr |

| participants |

- mean age 42 yrs (range not stated)

- eligibility criteria: ant thoracic or lumbar surgery, w/ ant

iliac crest harvest

- exclusion criteria: inappropriate ribs on preop x-ray,

severe neurological deficit, preexisting hip pain or

discomfort, mental illness

- total recruited: 54 pts (masking not stated); 39M:15F

|

| intervention |

autograft rib; 25 pts |

| comparison |

no iliac crest reconstruction, hemostatic bone wax; 29

pts |

| outcomes |

primary outcomes:

- donor site pain measured using VAS when lying still

on op side, & when active (2 wks, 3 mos postop);

pain measured using VAS when sleeping on op side

(1 yr)

- pt satisfaction w/ cosmesis (unsatisfied, moderately

satisfied, satisfied) (1 yr)

- pt comfort when wearing a belt w/ activity (uncomfortable,

moderately comfortable, comfortable) (1

yr)

- any clinical complications including fractures (w/in

1 yr)

(masking not stated)

|

| loss to FU |

none |

| funding/COI |

no declaration |

* Ant = anterior; COI = conflict of interest; FU = follow-up; pts = patients.

Posterior Harvest. Bojescul et al.5 used the "trapdoor" technique for their posterior iliac crest harvest. A 2 × 4 × 2–cm cortical window was created 8 cm from the

TABLE 5: Characteristics of Resnick study

| Characteristic |

Data |

| methods |

single-blinded RCT; duration 3 mos |

| participants |

- mean age 45 yrs (range not stated)

- smokers (29 of 30)

- eligibility criteria: 1- or 2-level ant cervical discectomy &

fusion, or 1-level cervical corpectomy, w/ ant iliac

crest harvest

- exclusion criteria: not stated

- total recruited: 30 pts (blinded); 19M:11F

|

| intervention |

morcellized β-TCP; 15 pts |

| comparison |

no iliac crest reconstruction, Gelfoam hemostatic agent;

15 pts |

| outcomes |

- primary outcomes: pain (immediately preop, & 24 hrs,

6 wks, & 3 mos postop) measured w/ patient-reported

McGill pain questionnaire (acute pain) & VAS (generalized

pain)

- secondary outcomes: plain x-ray appearance, cosmesis

as determined by surgeon (not blinded)

(masking not stated)

|

| loss to FU |

none |

| funding/COI |

supported by Orthovita, Inc. (Malvern, PA; manufacturer

of the intervention) |

Iliac crest reconstruction following harvest for spinal fusion

TABLE 6: Characteristics of Bojescul study

| Characteristic |

Data |

| methods |

double-blinded RCT; duration 1 yr |

| participants |

- mean age 35 yrs (range 23–67 yrs)

- eligibility criteria: spinal fusion, w/ posterior iliac crest

harvest

- exclusion criteria: pregnancy, peripheral vascular disease,

localized or systemic disease

- total recruited: 12 pts (blinded); 10M:2F

|

| intervention |

CHA; 5 pts |

| comparison |

no iliac crest reconstruction; 7 pts |

| outcomes |

- primary outcomes: donor site pain (predischarge, & at

6 wks, 3 mos, 6 mos, & 1 yr postop) measured w/

questionnaire (0, none; 1, mild; 2, medium; 3, moderate;

4, severe) and clinical palpation

- secondary outcomes: plain x-ray, CT, & SPECT appearance,

determined by 2 blinded observers

(masking not stated)

|

| loss to FU |

1 pt from each group |

| funding/COI |

none |

harvested. Patients in the investigative group received

sterile blocks and granulated CHA (Pro Osteon Implant

500). The reason for harvest was for spinal fusion (no further

details given).

Primary Outcome: Donor Site Pain

All studies examined donor site pain as a primary

outcome. Yang et al.33 reported decreased donor site pain

at 2 weeks and 3 months in patients with reconstruction

compared with those without reconstruction when active

(p < 0.05), but not when at rest (p > 0.05). At 1 year,

patients with reconstruction experienced less pain when

sleeping on the operative side (p < 0.05).

Resnick25 observed that the pain scores of patients

with reconstruction were significantly lower than those

in the control group in terms of both number and severity at the 6-week mark (p < 0.001). However, by 3 months,

as the pain scores of the group without reconstruction

diminished, a significant difference could no longer be

detected. The trend was only significant for the results of

the McGill pain questionnaire, but not the VAS.

TABLE 7: Assessment of potential bias in included RCTs*

| Criteria |

Yang et al. |

Resnick |

Bojescul et al. |

| random sequence generation (selection bias) |

+ |

? |

? |

| allocation concealment (selection bias) |

? |

? |

? |

| blinding of participants (performance bias) |

? |

+ |

+ |

| blinding of personnel (performance bias) |

? |

− |

+ |

| blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) |

? |

+ |

+ |

| incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) |

+ |

+ |

− |

| selective reporting (reporting bias) |

+ |

+ |

− |

| other potential sources of bias |

4 cases of Pott disease

in rib group |

almost all smokers |

age difference, very small nos. |

| summary assessment of risk of bias |

moderate |

moderate |

high |

* Using criteria as set out by Higgins and Green in the Cochrane Handbook. + = low risk of bias; − = high risk of bias; ? = unclear,

method not stated.

Bojescul et al.5 reported the donor site pain results at 1 year only, although they had also assessed pain at earlier time points (1 patient in each group was lost to follow-up). Three of 4 patients who underwent reconstruction reported no pain, and 1 reported mild pain. Of

the 6 patients without reconstruction, 2 subjectively had no pain, 1 had mild pain, in 2 it was medium, and in 1 moderate. Objective pain analysis yielded similar results, and did not reveal any statistical significance (p = 0.199)

TABLE 8: Characteristics of Bapat study

| Characteristic |

Data |

| methods |

NRCT; duration 1 yr

allocation according to surgical approach |

| participants |

- mean age 39 yrs (range not stated)

- eligibility criteria: spinal fusion of ant column, w/ ant

iliac crest harvest

- exclusion criteria: iliac defects < 25 mm, incomplete

neurological recovery, persistent sensory abnormalities

- total recruited: 36 pts (masking not stated); 10M:26F

|

| intervention |

autogenous rib graft; 20 pts (thoracotomy [16] or thoracophrenicolumbotomy

[6]) |

| comparison |

no iliac crest reconstruction; 16 pts (ant cervical corpectomy

[2], ant column reconstruction retroperitoneally

[2], thoracotomy [11], or thoracophrenicolumbotomy

[3]) |

| outcomes |

- primary outcomes: donor site pain (at 6-wk, 3-mo,

6-mo, & 12-mo FU) measured w/ questionnaire &

localized tenderness

- secondary outcomes: functional disability during routine

activities or sleeping on op side, cosmesis,

plain x-ray appearance, clinical complications (all

determined blinded)

|

| loss to FU |

2 pts from each group |

| funding/COI |

none |

TABLE 9: Characteristics of Epstein study

| Characteristic |

Data |

| methods |

NRCT; duration 2–3 yrs

allocation: first 23 pts no reconstruction, second 23 pts

reconstruction |

| participants |

- mean age 44 yrs (range 23–67 yrs)

- eligibility criteria: 1-level ant cervical corpectomy & fusion,

w/ iliac crest harvest

- exclusion criteria: not stated

- total recruited: 46 pts (masking not stated); 28M:18F

|

| intervention |

MacroPore sheet & ICM; 23 pts |

| comparison |

no iliac crest reconstruction, bone wax hemostatic

agent; 23 pts |

| outcomes |

- primary outcomes: bodily pain (1 wk preop, & 6 wks, 3

mos, 6 mos, & 12 mos postop) measured using

SF-36

- secondary outcomes: CT appearance (masking not

stated)

|

| loss to FU |

none |

| funding/COI |

no declaration |

Bapat et al.4 reported that 15% of patients with versus

69% of those without reconstruction had donor site pain

at the 1-year follow-up (p = 0.001), with patients who had

undergone reconstruction also experiencing significantly

lower intensity of pain (p < 0.001). Tenderness on palpation

was elicited in a similar percentage of patients (p =

0.003).

Epstein and Hollingsworth12 commented that postoperative

pain measured through SF-36 bodily pain scores

revealed comparable results over the course of 12 months,

with a trend toward greater improvement in the group

without reconstruction. However, no statistical analysis

was performed.

Secondary Outcomes

Quality of Life and Functional Disability. Yang et al.33

examined comfort when wearing a belt with activity at 1

year, asking patients to categorize according to uncomfortable,

moderately comfortable, and comfortable. More

patients who underwent reconstruction reported being

comfortable, and more patients without reconstruction

reported being uncomfortable (p < 0.05).

Bojescul et al.5 reported that no patients from either

group had functional impairment from donor site pain at

1-year follow-up. Bapat et al.4 found that patients without

reconstruction experienced donor site pain causing

discomfort while sleeping on the operative side (31%),

discomfort wearing trousers (18%), and a persistent limp

(6%) at 1 year. No patients in the group with reconstruction

reported these functional disabilities.

Epstein and Hollingsworth12 provided data on a range

of health and function parameters as measured through

SF-36 data. Outcomes appeared similar; however, no statistical

analyses were performed.

TABLE 10: Methodological assessment of included NRCTs*

| Criteria (max score) |

Bapat et al. |

Epstein & Hollingsworth |

| reporting (10) |

9 |

8 |

| external validity (3) |

2 |

1 |

| internal validity–bias (7) |

6 |

4 |

| internal validity–confounding (6) |

1 |

1 |

| power (1) |

0 |

0 |

| total (27) |

18 |

14 |

* According to the validated checklist developed by Downs and Black.

Cosmesis. Yang et al.33 asked patients to categorize

their level of satisfaction with donor site cosmesis at 1

year as unsatisfied, moderately satisfied, or satisfied. All

25 patients who underwent reconstruction reported being

moderately satisfied or satisfied, whereas 12 of the 29

patients without reconstruction reported being unsatisfied

(no statistical analysis). The authors noted that a number

of patients in the nonreconstructed but not in the reconstructed

group exhibited clear surface indentation at the

harvest site.

Resnick25 determined that there was no significant

difference in unblinded surgeon–determined cosmesis

at 3 months. Bapat et al.4 reported significantly poorer

cosmetic VAS scores for their nonreconstructed group

as determined by a blinded observer (p = 0.009), with a

significantly higher number of Grades 2 and 3 iliac crest

defects (p < 0.001).

Radiological Analysis. Yang et al.33 found no graft

displacement on x-ray studies obtained at 1 year for their

rib-reconstructed group. Resnick25 reported that x-ray

evaluation of graft defects was not a useful method of

assessment.

Bojescul et al.5 found that 3 of 4 patients who underwent

CHA reconstruction (1 was lost to follow-up) had

evidence of bony ingrowth on x-ray and CT studies at

1 year. All had biological activity on bone scans. This

compared with 1 of 6 patients without reconstruction who

had bony ingrowth on x-ray and CT studies (p = 0.190),

and no patients with biological activity on bone scans (p

= 0.0048).

Bapat et al.4 reported that 19 of 20 rib grafts achieved

fusion at 6 months, evaluated primarily by x-ray studies.

One patient experienced graft resorption, and another

experienced graft displacement, whereas a third patient

suffered an iliac crest fracture intraoperatively during

graft impaction, and was reassigned to the nonintervention

group.

Epstein and Hollingsworth12 reported 100% fusion at

6 months in their reconstructed group as determined on

CT studies. Ectopic bone formation was observed to be

severe in 9%, moderate in 35%, and mild in 56% of cases,

but did not adversely affect outcome.

Resource Use. Only Epstein and Hollingsworth12 reported

results for this outcome, despite it not being mentioned

in the protocol. Hospital stay for the reconstructed

group was 3.6 days, compared with 3.2 days for the non-reconstructed group, leading the authors to conclude thatno difference existed (no statistical analysis). The baseline

operating time of 3 hours was increased by a mean of

24 minutes in the reconstructed group.

Postoperative Complications. Yang et al.33 reported

no complications for both groups. Resnick25 reported on

1 patient from the nonreconstructed group who experienced

a graft site infection requiring suture removal and

oral antibiotics. Bojescul et al.5 reported 1 superficial

infection of the harvest site in the reconstructed group,

which did not involve the implant. Bapat et al.4 reported

5 complications (31%) in 16 cases without reconstruction.

The complications were skin tenting and pressure necrosis,

bursitis, scar hypertrophy, infection, and persistent

limp. There were no complications in the reconstructed

group.

Discussion

Summary of Evidence

As far as we are aware, this review is the first attempt

to evaluate systematically the evidence for reconstruction

following iliac crest harvesting for spinal procedures.

Currently, there is insufficient high-quality evidence to

determine definitively the clinical utility of donor site

reconstruction following harvest for spinal procedures.

However, the best available data identified through this

systematic review suggest that iliac crest reconstruction

may be useful in reducing postoperative pain, minimizing

functional disability, and improving cosmesis. No pattern

of other clinical, radiological, or resource outcomes was

identified.

Limitations of This Review

The strength of any review relies on the quality of

the studies it examines. In this systematic review we identified

5 studies comparing reconstructive against no reconstructive

intervention for iatrogenic iliac crest defects.

Three studies were RCTs (totaling 96 patients) and 2 were

NRCTs (totaling 82 patients). All examined iliac crest

harvesting in the context of spinal fusion procedures.

Critical evaluation of the included studies revealed a

moderate to high risk of bias, especially in the NRCTs,

which were particularly prone to poor internal validity,

with a high risk of selection bias and confounding. Although

we decided to include these latter studies due to

the anticipated small number of RCTs, the specific limitations

of these NRCTs should be borne in mind when

evaluating their results.

Additional limitations include heterogeneity between

studies, such as patient population, level of spine operated

on (and hence size of defect), site of iliac crest grafting

(anterior vs posterior harvesting), harvesting technique,

reconstruction technique and type of graft used, method

of outcome evaluation, and the small number of patients

involved. As a result, specific questions such as harvesting

or reconstruction technique could not be evaluated.

Although we broadened our search strategy by not

applying any language restrictions, performing extensive

cross-referencing of relevant studies, and a search for recently completed or ongoing trials, our review is susceptible

to publication bias because we did not include an

extensive search for so-called gray literature. Studies that

did not show an effect for reconstruction would be most

likely to remain unpublished.

Conclusions

The evidence supporting reconstruction following

iliac crest harvest for spinal fusion is poor. However,

the best available evidence identified in this systematic

review supports the notion that iliac crest reconstruction

following harvest for spinal fusion may reduce postoperative

pain, minimize functional disability, and improve

cosmesis. The optimal type of graft material or surgical

technique was not investigated, and remains a relevant

question for future clinical studies.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest or sources of funding.

Author contributions to the study and manuscript preparation

include the following. Conception and design: Chau. Acquisition

of data: Chau, Xu. Analysis and interpretation of data: Chau, Xu,

Gragnaniello. Drafting the article: Chau, Xu, Van Der Rijt. Critically

revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of

manuscript: all authors. Approved the final version of the manuscript

on behalf of all authors: Chau. Administrative/technical/material

support:

Chau, Xu, Gragnaniello. Study supervision: Chau, Van Der

Rijt, Wong, Gragnaniello, Stanford, Mobbs.

References

- Acharya NK, Mahajan CV, Kumar RJ, Varma HK, Menon

VK: Can iliac crest reconstruction reduce donor site morbidity?:

a study using degradable hydroxyapatite-bioactive glass

ceramic composite. J Spinal Disord Tech 23:266–271, 2010

- Ahlmann E, Patzakis M, Roidis N, Shepherd L, Holtom P:

Comparison of anterior and posterior iliac crest bone grafts

in terms of harvest-site morbidity and functional outcomes. J

Bone Joint Surg Am 84-A:716–720, 2002

- Asano S, Kaneda K, Satoh S, Abumi K, Hashimoto T, Fujiya

M: Reconstruction of an iliac crest defect with a bioactive ceramic

prosthesis. Eur Spine J 3:39–44, 1994

- Bapat MR, Chaudhary K, Garg H, Laheri V: Reconstruction

of large iliac crest defects after graft harvest using autogenous

rib graft: a prospective controlled study. Spine 33:2570–2575,

2008

- Bojescul JA, Polly DW Jr, Kuklo TR, Allen TW, Wieand KE:

Backfill for iliac-crest donor sites: a prospective, randomized

study of coralline hydroxyapatite. Am J Orthop 34:377–382,

2005

- Chau AMT, Mobbs RJ: Bone graft substitutes in anterior cervical

discectomy and fusion. Eur Spine J 18:449–464, 2009

- Dave BR, Modi HN, Gupta A, Nanda A: Reconstruction of

iliac crest with rib to prevent donor site complications: a prospective

study of 26 cases. Indian J Orthop 41:180–182,

2007

- Defino HL, Rodriguez-Fuentes AE: Reconstruction of anterior

iliac crest bone graft donor sites: presentation of a surgical

technique. Eur Spine J 8:491–494, 1999

- Delawi D, Dhert WJA, Castelein RM, Verbout AJ, Oner FC:

The incidence of donor site pain after bone graft harvesting

from the posterior iliac crest may be overestimated: a study on

spine fracture patients. Spine 32:1865–1868, 2007

- Downs SH, Black N: The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised

and non-randomised studies of health care interventions.

J Epidemiol Community Health 52:377–384, 1998

- Dusseldorp JR, Mobbs RJ: Iliac crest reconstruction to reduce

donor-site morbidity: technical note. Eur Spine J 18:1386–

1390, 2009

- Epstein NE, Hollingsworth R: Does donor site reconstruction

following anterior cervical surgery diminish postoperative

pain? J Spinal Disord Tech 16:20–26, 2003

- Gil-Albarova J, Gil-Albarova R: Donor site reconstruction in

iliac crest tricortical bone graft: surgical technique. Injury

[epub ahead of print], 2011

- Hardy JH: Iliac crest reconstruction following full-thickness

graft: a preliminary note. Clin Orthop Relat Res (123):32–

33, 1977

- Harris MB, Davis J, Gertzbein SD: Iliac crest reconstruction

after tricortical graft harvesting. J Spinal Disord 7:216–221,

1994

- Higgins JPT, Green S (eds): Cochrane Handbook for Systematic

Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 [updated

March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 (http://www.

cochrane-handbook.org/) [Accessed March 13, 2012]

- Hochschuler SH, Guyer RD, Stith WJ, Ohnmeiss DD, Rashbaum

RF, Johnson RG: Proplast reconstruction of iliac crest

defects. Spine 13:378–379, 1988

- Howard JM, Glassman SD, Carreon LY: Posterior iliac crest

pain after posterolateral fusion with or without iliac crest

graft harvest. Spine J 11:534–537, 2011

- Ito M, Abumi K, Moridaira H, Shono Y, Kotani Y, Minami

A, et al: Iliac crest reconstruction with a bioactive ceramic

spacer. Eur Spine J 14:99–102, 2005

- Kim DH, Rhim R, Li L, Martha J, Swaim BH, Banco RJ, et

al: Prospective study of iliac crest bone graft harvest site pain

and morbidity. Spine J 9:886–892, 2009

- Lubicky JP, DeWald RL: Methylmethacrylate reconstruction

of large iliac crest bone graft donor sites. Clin Orthop Relat

Res 164:252–256, 1982

- Morgan SJ, Jeray KJ, Saliman LH, Miller HJ, Williams AE,

Tanner SL, et al: Continuous infusion of local anesthetic at

iliac crest bone-graft sites for postoperative pain relief. A

randomized, double-blind study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:

2606–2612, 2006

- National Health and Medical Research Council: NHMRC

Levels of Evidence and Grades for Recommendations

for Developers of Guidelines, December 2009. Australian

Government National Health and Medical Research Council,

2009 (http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/guidelines/

evidence_statement_form.pdf) [Accessed March 13, 2012]

- Pollock R, Alcelik I, Bhatia C, Chuter G, Lingutla K, Budithi

C, et al: Donor site morbidity following iliac crest bone harvesting cervical fusion: a comparison between minimally

invasive and open techniques. Eur Spine J 17:845–852, 2008

- Resnick DK: Reconstruction of anterior iliac crest after bone

graft harvest decreases pain: a randomized, controlled clinical

trial. Neurosurgery 57:526–529, 2005

- Schwartz CE, Martha JF, Kowalski P, Wang DA, Bode R, Li

L, et al: Prospective evaluation of chronic pain associated

with posterior autologous iliac crest bone graft harvest and

its effect on postoperative outcome. Health Qual Life Outcomes

7:49, 2009

- Sengupta DK, Truumees E, Patel CK, Kazmierczak C, Hughes

B, Elders G, et al: Outcome of local bone versus autogenous

iliac crest bone graft in the instrumented posterolateral fusion

of the lumbar spine. Spine 31:985–991, 2006

- Silber JS, Anderson DG, Daffner SD, Brislin BT, Leland JM,

Hilibrand AS, et al: Donor site morbidity after anterior iliac

crest bone harvest for single-level anterior cervical discectomy

and fusion. Spine 28:134–139, 2003

- Singh K, Phillips FM, Kuo E, Campbell M: A prospective,

randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of postoperative

continuous local anesthetic infusion at the iliac crest bone

graft site after posterior spinal arthrodesis: a minimum of

4-year follow-up. Spine 32:2790–2796, 2007

- Tanishima T, Yoshimasu N, Ogai M: A technique for prevention

of donor site pain associated with harvesting iliac bone

grafts. Surg Neurol 44:131–132, 1995

- Wai EK, Sathiaseelan S, O'Neil J, Simchison BL: Local administration

of morphine for analgesia after autogenous anterior

or posterior iliac crest bone graft harvest for spinal fusion:

a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled

study. Anesth Analg 110:928–933, 2010

- Wang MY, Levi ADO, Shah S, Green BA: Polylactic acid

mesh reconstruction of the anterior iliac crest after bone harvesting

reduces early postoperative pain after anterior cervical

fusion surgery. Neurosurgery 51:413–416, 2002

- Yang Y, Chen X, Zan Z, Tang H, Huang Y, Tang L, et al:

[Clinical application of rib autograft for iliac crest reconstruction

by anterior approach of thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.]

Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 23:1334–

1337, 2009 (Chinese)

Manuscript submitted November 17, 2011.

Accepted March 12, 2012.

Please include this information when citing this paper: published

online April 13, 2012; DOI: 10.3171/2012.3.SPINE11979.

Address correspondence to: Ralph J. Mobbs, M.B.B.S., M.S.,

F.R.A.C.S., Suite 7a, Level 7, Prince of Wales Private Hospital,

Randwick, New South Wales 2031, Australia. email: ralphmobbs@hotmail.com.

Reconstruction iliac crest defects following harvest for spinal fusion: a systematic review Reconstruction iliac crest defects following harvest for spinal fusion: a systematic review

You will need the Adobe Reader to view and print the above documents.

|