|

Technique, challenges and indications for percutaneous pedicle screw fixation

Ralph J. Mobbs a,*, Praveenan Sivabalan b, Jane Li b

- Department of Neurosurgery, Prince of Wales Private Hospital, Suite 3, Level 7, Sydney Spine Clinic, Randwick, New South Wales 2031, Australia

- Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

Minimally invasive techniques in spinal surgery are increasing in popularity due to numerous potential

advantages, including reduced length of stay, blood loss and requirements for post-operative analgesia as

well as earlier return to work. This review discusses guidelines for safe implantation of percutaneous

pedicle screws using an image intensifier technique. As indications for percutaneous pedicle screw techniques

expand, the nuances of the minimally invasive surgery technique will also expand. It is paramount

that experienced surgeons share their collective knowledge to assist surgeons at their early attempts of

these complex, and potentially dangerous, procedures. Technical challenges of percutaneous pedicle

screw fixation techniques are also discussed including: small pedicle cannulation, percutaneous rod

insertion for multilevel constructs, incision selection for multilevel constructs, changing direction with

percutaneous pedicle screw placement, L5/S1 screw head proximity and sclerotic pedicles with difficult

Jamshidi placement. We discuss potential indications for minimally invasive fusion techniques for complex

spinal surgery and support these with descriptions of illustrative patients.

Crown Copyright © 2010 Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Pedicle screw instrumentation enables a rigid construct to promote

stability and fusion for numerous spinal pathologies including:

trauma, tumours, deformity and degenerative disease. The

safety of traditional open techniques for pedicle screw placement

has been well documented; however, due to the advantages of

minimally invasive surgery (MIS), demand for percutaneous pedicle

screw insertion will increase. Improvements in minimally invasive

instrumentation have also broadened the scope of spinal

disorders that surgeons can operate on.1,2

Percutaneous pedicle screw insertion can be an intimidating

prospect for surgeons who have been trained in open techniques

only. The initial change has a steep learning curve; however, there

are several basic principles that can assist the surgeon in safe

placement of the Jamshidi needle into a thoracic or lumbar pedicle.

2. Open versus minimally invasive surgery

Conventional open spine surgery has several reported limitations

including extensive blood loss, post-operative muscle pain

and infection risk. The paraspinal muscle dissection involved in

open spine surgery (Fig. 1) can cause muscular denervation, increased

intramuscular pressure, ischaemia, necrosis and revascularisation injury resulting in muscle atrophy and scarring, often

associated with prolonged post-operative pain and disability.

Spinal fixation utilising muscle-dilating approaches (Figs. 1 and

2) to minimise surgical incision length, surgical cavity size and

the amount of iatrogenic soft-tissue injury associated with surgical

spinal exposure, without compromising outcomes, is thus a desirable

advancement.3–12

No published articles of high-quality show that MIS is superior

to open spinal surgery; however, there is a trend towards MIS of

the spine due to lower complication rates and approach-related

morbidity, with minimal soft tissue trauma, reduced intra-operative

blood loss/risk of transfusion, improved cosmesis, decreased

post-operative pain and narcotic usage, shorter hospital stays with

faster return to work and thus reduced overall health care

costs.1,4,6–9,13,14 Despite this, some reports believe that minimal

exposure is associated with incomplete treatment of pathology,13

due to significantly decreased visualisation with MIS.10 Another

potential limitation includes the use of imaging-guided pedicle

screw placement. Imaging increases operating times and patient/

surgeon exposure to ionising radiation. Non-radiological navigation

methods thus need to be explored to further improve MIS.3,10

The senior author (RJ Mobbs) has inserted more than 700 percutaneous

pedicle screws (Fig. 2) with two significantly misplaced

screws (0.29%), and one screw placement resulting in a permanent

nerve root injury with a pedicle fracture (0.14%). Both complications

were within the initial 10 patients, representing a steep

learning curve with this technique.

3. Percutaneous placement of pedicle screws

The technique described here uses intra-operative radiography

(image intensifier [II]). The senior author also uses intra-operative

CT-based stereotactic guidance for pedicle screw placement; however,

there is a greater degree of accuracy with the use of II for pedicle

cannulation (RJ Mobbs, unpublished data). For small thoracic

pedicles, the senior author only uses II due to the enhanced accuracy

with this technique.

The sequence of percutaneous placement of pedicle screw

insertion is described as follows (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 1. Open versus (vs.) minimally invasive surgery (MIS) technique for pedicle

screw insertion showing: (a) normal anatomy; (b) muscle retraction with

traditional ''open'' surgery vs. (c) ''tubular retractors'' with percutaneous pedicle

screws.

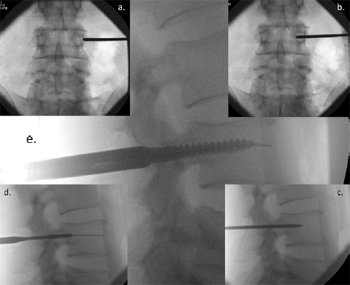

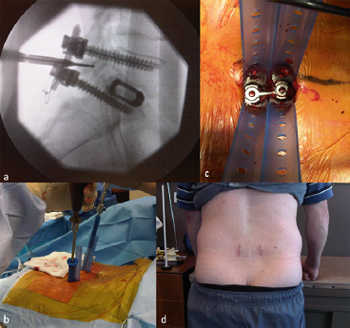

Fig. 2. Image Intensifier radiographs of the percutaneous technique for pedicle screw

insertion showing: (a) anterior/posterior (AP) view of the Jamshidi needle docked

onto the lateral aspect of the pedicle – the ''3 o'clock position''; (b) AP view of

advancement of the needle 20 mmto 25 mminto the vertebral body; (c) lateral view,

checking the position of the Jamshidi needle in lateral view; (d) lateral view, the Kwire

and tapping of the pedicle; and (e) lateral view, insertion of the pedicle screw.

Fig. 3. Diagrams illustrating the anatomical principles of percutaneous pedicle

screw insertion: views from top to bottom: (a) superior, (b) posterior, (c) lateral, (d)

superior. First the initial skin incision is made with the patients' body habitus in

mind. Second, the Jamshidi needle is first ''docked'' onto the lateral aspect of the

pedicle – ''position 1'' – on the anterior/posterior image intensifier (II) radiograph

projection. Third, the Jamshidi needle is advanced 20 mm to 25 mm so that the

needle is beyond the medial border of the pedicle and into the vertebral body – to

''position 3''. Finally, the position is confirmed by lateral II radiograph projection

before insertion of the K-wire.

- Place the II in the anterior/posterior (AP) position. The spinous

process should be midline between the pedicles to

ensure a direct AP projection (Fig. 2a).

- Mark the position of the lateral aspect of the pedicle on the

skin. Depending upon the depth of the tissue between skin

and pedicle, the skin incision should be made laterally

(Fig. 3) so that the Jamshidi needle can be angled appropriately

when inserting it into the pedicle.

- Place the Jamshidi needle through the skin incision and

''dock'' onto the lateral aspect of the pedicle (Fig. 2a). This

is called the ''3 o-clock'' position.

- Advance the Jamshidi needle 20 mm to 25 mm into the pedicle,

making sure the needle remains lateral to the medial

pedicle wall (Figs. 2b and 3).

- Position the II in the lateral plane. The Jamshidi needle

should now be in the vertebral body, and therefore ''safe''

with no risk of medial pedicle breach (Fig. 2c).

- Place a K-wire down the Jamshidi needle and place a pedicle

tap down the trajectory of the K-wire (Fig. 2d).

- Place the final pedicle screw with the screw placed down the

K-wire (Fig. 2e), making sure not to advance the K-wire

beyond the anterior aspect of the vertebral body.

4. Challenges unique to MIS/percutaneous pedicle screw

insertion

There are many technical challenges unique to the percutaneous

pedicle screw insertion technique. After the surgeon is comfortable

with MIS techniques for single-level degenerative

pathologies, the temptation is to attempt more difficult multi-level

constructs such as those required in patients with tumour and

trauma pathologies.

The senior author has identified common challenges described in the following sections.

4.1. Changing direction of screw placement following initial pedicle cannulation

Following initial placement of the Jamshidi needle into the vertebral

body, the lateral projection may demonstrate a poor trajectory

that the surgeon may wish to correct. Using the pedicle tap

placed down the K-wire, the surgeon can ''redirect'' the tap along

a more appropriate trajectory, using an undersized tap (Fig. 4). This will result in an acute bend in the K-wire distal to the tap. Care

should be taken not to bend the K-wire too much (Fig. 4b). With

the tap advanced into the vertebral body, the K-wire can be removed

and then a fresh ''straight'' K-wire reintroduced down the

tap into the new position (Fig. 4c). The pedicle screw can then be

placed down the K-wire in the new trajectory.

4.2. L5/S1 screw head proximity

The percutaneous technique can be difficult at the L5/S1 level

due to the L5 and S1 pedicle angulations. The percutaneous retraction

sleeves can impinge on one another at skin level. The options

for dealing with this common problem include either placing the

S1 pedicle screw in a more inferior starting position, or to use

''flexible'' retraction sleeves (Fig. 5) so that the sleeves can be deflected

at skin level and not impinge on each other.

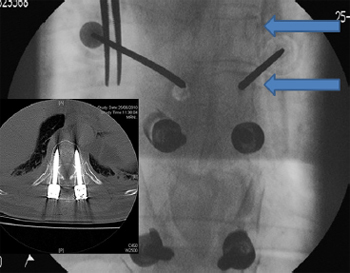

4.3. Cannulation of small pedicles

The senior author has placed percutaneous pedicle screws as

high as T4 in patients with tumour and trauma; however, percutaneous

pedicle placement high in the thoracic spine can be technically

difficult due to the small pedicle sizes in the mid-upper thoracic

spine and the change in pedicle angulation at the T1 to T4 levels.

The greatest challenge, however, for percutaneous placement in

the thoracic spine is from small pedicles. Cannulation of small pedicles

involves careful evaluation of the pre-operative CT scans and

and AP radiographs to ensure that the pedicle can be cannulated.

The pedicle must have a width of at least 3 mm to 4 mm so that

the Jamshidi needle can be navigated down the pedicle. The surgeon

must have an excellent view of the pedicle prior to attempting cannulation

of a small diameter pedicle. This involves small movements

of the gantry of the II machine so that the II is directed in a ''bull's

eye'' view down the pedicle (Fig. 6). Due to the greater degree of

accuracy of the II technique (Fig. 6) over stereotaxis, the senior

author recommends II for small pedicle cannulation.

Fig. 4. Image Intensifier lateral radiographs showing changing direction of screw

placement following initial pedicle cannulation. (a) The Jamshidi needle has

cannulated the pedicle and vertebral body. On review of the lateral X-ray image, the

surgeon decides to re-direct the screw into a position that is more parallel with the

endplate. (b) After K-wire insertion, an undersized tap can be used to force the Kwire

into a more appropriate direction, taking care to avoid bending the K-wire too

much. (c) With the tap in place, the K-wire can be removed and replaced with a

new, straight K-wire down the tap in the new direction.

4.4. Skin Incision selection for multi-segmental fixation

Multi-segmental fixation procedures have numerous nuances

that can make the surgeon's life much easier. The first thought is incision selection, as incisions that ''line-up'' in a straight line

(Fig. 7) represent a far easier prospect for rod insertion. The qualification

here is for patients who have a scoliosis, or trauma, where

the pedicles may not line up in a straight line. For a single-level fixation,

the rod insertion is not difficult and is usually not a problem.

For multi-level fixation, a staggered line of incision points can result

in a difficult rod insertion.

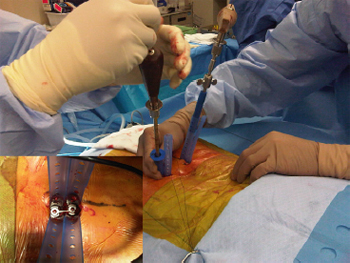

Fig. 5. Intra-operative photographs showing the use of retraction sleeves to avoid

screw head proximity at L5/S1. Flexible retraction sleeves simplify the problem of

screw head proximity as the retractors can easily be deflected and not ''get in your

way'' with percutaneous pedicle screw placement. It is common at L5/S1 for the

surgeon to require a single incision only as the retraction sleeves are in the same

position at the skin edge. (Insert) Aerial view.

Fig. 6. Anterior/posterior image intensifier (II) radiographs showing percutaneous

cannulation of small pedicles. Angulating the II machine so that the surgeon is

looking down the pedicle – the ''bulls eye'' view (arrows) – assists in placement in

difficult pedicles. (Insert) The II technique results in highly accurate pedicle screw

insertion – a 5.5 mm screw into a 6 mm pedicle.

Fig. 7. Intra-operative photograph of skin incision for multi-level constructs. The

black line is showing all four incisions along a straight trajectory – making the

insertion of the rod technically much easier. The white line shows the incisions in a

staggered fashion – the rod insertion here will be more difficult.

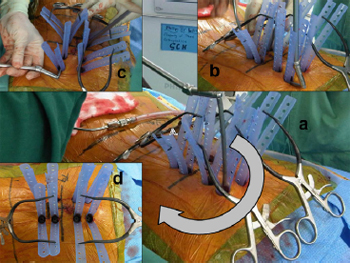

4.5. Insertion of a rod for multi-segmental fixation

Rod insertion for multi-segmental fixation involves the surgeon

having a brief mental checklist prior to insertion. Removing the rod

after an initial placement can be difficult and time consuming if the

surgeon has to change the length or curvature of the rod prior to a

re-insertion. The checklist includes:

Fig. 8. Intra-operative photographs showing insertion of rod in a patient requiring

multi-level surgery. (a) Rod insertion can be performed with a semicircular

technique (arrows), making sure that the rod is under the fascial layer with (b, c)

advancing the rod. Always start the insertion at the pedicle screw head that is most

superficial/closest to the skin. (d) Aerial view.

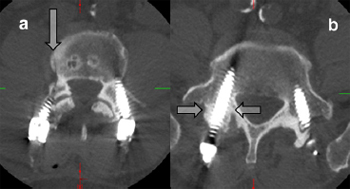

Fig. 9. Axial CT scans showing sclerotic pedicles that may result in the necessity for

screw placement using an open technique. (a) The arrow points towards a Jamshidi

needle tract created when the Jamshidi needle ''hit'' a sclerotic bar of bone between

the pedicle and vertebral body – safe cannulation of the pedicle/vertebral body

could not be achieved and a high-speed drill was used to cannulate the pedicle. (b)

This pedicle (arrows) was sclerotic – Jamshidi placement required an open screw

positioning.

- How long should the rod be? The length between the retraction

sleeves should provide a guide to rod length.

- Does the rod require bending before insertion? As a general

rule, the surgeon should try to leave the pedicle screw heads

at an equivalent height throughout the construct to aid with

ease of rod insertion. The exception here is with trauma

where a reduction manoeuvre may be required.

- Initially from which end should the rod be inserted? The rod

should be inserted from the end of the construct where the

pedicle screw head is closest to the skin, enabling ease of

insertion and navigation along the pedicle screw heads

(Fig. 8).

- Do I need an additional incision to insert the rod? This is

usually not necessary as the rod can be inserted over many

levels via the cranial incision which is usually the most

superficial of the pedicle screw insertions.

4.6. Sclerotic pedicle – difficult Jamshidi placement in hard pedicles

Pedicles that are sclerotic or osteopetrotic (''ivory bone'') can be

difficult in terms of Jamshidi placement. Advancing a Jamshidi into

these pedicles can be frustrating – rarely the percutaneous technique needs to be abandoned and an open technique with

direct cannulation of the pedicle with a high-speed drill is required

(Fig. 9).

5. Indications for percutaneous pedicle screw insertion

5.1. Degenerative spine disorders

Paraspinal muscle retraction allowing adequate exposure in

open procedures is a primary cause of post-laminectomy syndrome

and ''fusion disease''.11,12 Since the first endoscopic lumbar

discectomy in 1991, MIS has been used to routinely treat degenerative

spinal pathologies including; herniated disc removal, spinal

stenosis decompression and/or fusion aiming to avoid these problems.

Preliminary clinical outcomes suggest MIS is as efficacious as

open spinal surgery for degenerative spinal disorders, with added

advantages of reduced recovery times, pain and days to return to

work. However, as the use of MIS in complex spinal surgery is only

in its infancy, these favourable results are largely anecdotal and yet

to be validated by long-term outcome studies.4,11

MIS fusion is indicated for mechanical lower back-pain and

grade I and II spondylolisthesis-associated radicular pain

(Fig. 10). Higher grade spondylolistheses prove more challenging

and open approaches are recommended for optimal management.

14 Harris et al.'s3 comparison of 29 patients receiving single/

double level posterolateral percutaneous instrumented fusion

for symptomatic spondylolisthesis with published open fusion results

revealed comparable improvements in pain and disability,

whereas mean blood loss and operating time were significantly

lower with the use of MIS (222 mL vs. 1517 mL; 141 minutes vs.

298 minutes).3

MIS is also indicated for recurrent disc herniation, pseudoarthrosis

and severe discogenic lower back pain15 resulting from

post-laminectomy instability or spinal trauma.14

5.1.1. Illustrative patient 1

A 73-year-old male presented with neurogenic claudication and

mechanical lower back pain of 3 years' duration. Imaging revealed

severe canal stenosis at L4/5 due to spondylolisthesis, and facet joint/ligamentous hypertrophy. A midline incision and posterior

lumbar interbody fusion was performed. The midline incision was

closed and percutaneous screws inserted using the II technique.

Blood loss was 180 mL with discharge from hospital on day 4.

Fig. 10. Middle panel. Post-operative photograph of illustrative patient 1, a 73-

year-old male who presented with L4/5 degenerative spondylolisthesis with

neurogenic claudication. (a) Lateral image intensifier (II) radiograph showing Grade

I spondylolisthesis; (b) sagittal T2-weighted MRI showing severe canal stenosis; (c)

photograph at 8 weeks showing post-operative incision; (d) lateral II image

showing initial midline incision and posterior lumbar interbody fusion; (e) lateral II

percutaneous pedicle screw fixation pre-reduction; and (f) lateral II final radiograph

showing reduction of spondylolisthesis.

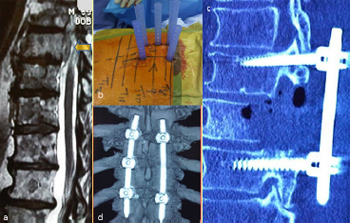

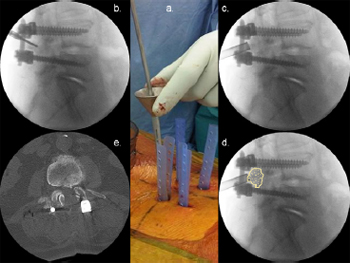

Fig. 11. Illustrative patient 2, a 17-year-old male who presented with a T12

American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) – A spinal cord injury following a high

velocity motorcycle accident. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI showing T12 spinal

injury with ASIA – A neurological deficit; (b) intra-operative photograph showing

percutaneous pedicle screw fixation; (c) anterior/posterior image intensifier (II)

radiograph and (d) lateral II radiograph showing stabilisation; and (e) postoperative

photograph showing early mobility within 24 hours.

5.2. Trauma

Traumatic spinal injuries are often associated with high velocity,

high energy impacts, (e.g. falls, motor vehicle crashes). Early

surgical intervention may prevent or potentially reverse neurological

deterioration.4 Surgical management involves decompression,

reduction, anterior column support if necessary, restoration of posterior

tension band and fusion to prevent spinal deformity developing

while providing immediate spinal stability.4,16 Current

surgical spine trauma treatment is predominantly open surgery

with instrumentation and fusion.16 Trauma patients, however,

are at greater risk of intra-operative blood loss with infection rates

of 0.7% to 10%. These vulnerabilities, along with other comorbidities

and the strong likelihood of systemic injuries in spinal trauma

patients, make MIS approaches highly valuable for minimising access-

related morbidity.4,16

Percutaneous instrumentation with/without fusion is performed

following thoracolumbar injuries for spinal stabilisation.4

Thoracic pedicle screw utilisation for degenerative and traumatic

injuries is one of the newest developments in MIS; however, morbidity

associated with screw misplacement in the thoracic spine is

greater than for the lumbar spine as there is greater risk of spinal

cord lesions, paraplegia, and fatal great vessel injury.13

Posterior MIS spinal fusion approaches such as posterior pedicle

screw/rod fixation are being applied to thoracic spine fracture

management (Fig. 11), providing stand-alone fixation of stable

burst or flexion distraction injuries. Temporary percutaneous posterior

fixation can enable mobilisation and prevent secondary injury

when there is an unstable injury and complete fixation is

contraindicated. Despite these developments, there are no established

MIS techniques in thoracic spine trauma surgery.16

5.2.1. Illustrative patient 2

A 17-year-old male presented with a T12 American Spinal

Injury Association–A spinal cord injury following a high velocity motorcycle accident. Stabilisation surgery was performed the day

of presentation with mobilisation and wheelchair rehabilitation

within 24 hours (Fig. 11). Surgical time was 2 hours, 5 minutes

with 80 mL of blood loss. The patient requested pedicle screw removal

12 months following surgery due to discomfort of the pedicle

screw tulips against his wheelchair.

5.3. Spinal neoplasia

Up to 70% of cancer patients show evidence of metastatic disease

at death, with 40% having spinal involvement.6 Improvements

in systemic cancer management and imaging is expected to increase

the incidence of spinal metastases detection.4 Metastatic

spine disease arises most commonly in the thoracic spine (thoracic

70%; lumbar 20%; cervical 10%) with 10% to 20% suffering symptomatic

cord compression causing neurological dysfunction and

debilitating pain requiring treatment.4,6

Studies on metastatic spinal disease show better functional outcomes

following surgical decompression/stabilisation prior to radiation

than radiation alone (84% vs. 57%). Surgery prolongs survival,

maintains continence and reduces corticosteroids and analgesic

use.6 Oncology patients often suffer multiple comorbidities, so efforts

to reduce surgical morbidity are essential.16 Although treatment

is often palliative, it is crucial in improving quality of life

(QOL) by improving pain and ambulatory function.4 Thus, the

advantages of MIS, including smaller incisions limiting wound

complications, are crucial for maintaining/improving the QOL of

cancer patients with a mean survival of only 8 to 12 months.4,6

Another recently introduced stabilisation technique for spinal

neoplasia utilises percutaneous instrumentation with cement

reconstruction and/or placement of intervertebral structural grafts.

The combination of increasingly available MIS management options

(Fig. 12), and chemo/radiotherapy will likely improve spinal

cancer treatment.4

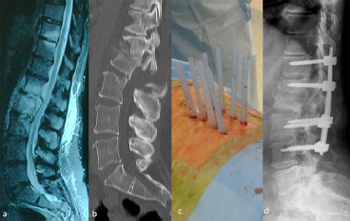

5.3.1. Illustrative patient 3

A 69-year-old male presented with progressive paraparesis and

cord compression at T9. He had metastatic lung cancer with an expected

longevity of less than 12 months. MIS decompression was

proposed; however, stabilisation was recommended due to the

anterior compression and pediculectomy/partial vertebrectomy

necessary for adequate tumour resection. Surgical time was 2

hours and 35 minutes with 210 mL of blood loss and a length of stay (LOS) of 5 days. The patient remained independently mobile

until his death 7 months following surgery.

5.4. Infection

Vertebral osteomyelitis is relatively uncommon, accounting for

3% of total osteomyelitis; however, its incidence worldwide is

growing and it causes substantial morbidity.17,18 Osteomyelitis of

the thoracic spine causes vertebral body collapse and thus spinal

cord compromise or kyphosis.16 Surgical indications exist,

although most treatment is conservative, utilising antibiotics.

These indications include the need for bacterial diagnosis when

other methods fail, abscess drainage, decompression of neural elements

causing worsening neurological deficit, debridement of persisting

infection and restoration and/or maintenance of spinal

alignment and stability.16–18

Current surgical management of osteomyelitis includes thoracotomy,

corpectomy and reconstruction. Open anterior thoracic

spine exposure for vertebral osteomyelitis is associated with high

mortality,16,17 partly due to the frequent occurrence of vertebral

osteomyelitis in the elderly, the debilitated and patients with multiple

comorbidities. Thus MIS can potentially improve outcomes

(Fig. 13).17

A small study of patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis,

who were treated with thoracoscopic debridement, decompression

and anterior fusion with no disease recurrence after two years,

suggested the feasibility of MIS for vertebral osteomyelitis.17 Larger

studies are required to further deduce whether MIS is beneficial

as only small MIS studies for vertebral osteomyelitis with

short-term follow-up exist.17

5.4.1. Illustrative patient 4

A 47-year-old woman positive for hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency

virus presented with L1/L2 osteomyelitis. The patient

had developed progressive pain and leg weakness over 2 months

with vertebral body collapse and gross mechanical instability at

L1/L2. Open surgery was not offered due to her pre-morbid status

and high-risk to the surgical team. Percutaneous stabilisation of

the progressive kyphosis/vertebral body collapse was offered. Surgical

time was 1 hour, 55 minutes with 120 mL of blood loss. The patient

was mobilised on day 1 with significantly reduced pain scores

and discharged to the infectious diseases team. Follow-up at 4

months revealed bone union across the L1/L2 interspace.

Fig. 12. Illustrative patient 2, a 69-year-old male who presented with progressive

paraparesis and cord compression at T9. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI showing T9

cord compression from lung metastasis (arrow); (b) intra-operative photograph

showing percutaneous screw fixation; (c) sagittal post-operative CT scan reconstruction

showing partial vertebrectomy and decompression; and (d) post-operative

three-dimensional CT scan reconstruction showing stabilisation.

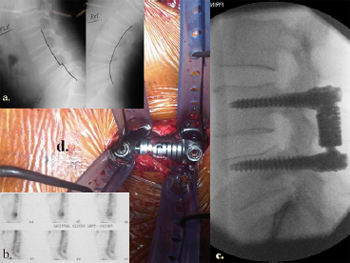

Fig. 13. Illustrative patient 4, a 47-year-old female, positive for hepatitis C and

human immunodeficiency virus, with L1/L2 osteomyelitis. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted

MRI showing L1/L2 osteomyelitis; (b) sagittal CT scan reconstruction showing

progressive kyphosis; (c) intra-operative photograph showing percutaneous pedicle

screw fixation; and (d) post-operative lateral image intensifier radiograph showing

a reduction of deformity and restoration of sagittal alignment.

5.5. Obesity

All spinal operations prove more difficult in patients with obesity,

9 and they have increased complication risks including surgical

site infection following fusion. However, MIS posterior lumbar fusion

is especially useful for these patients.13,19 Open posterior lumbar

fusions require longer incisions to access the deeper spine in

obese patients.9,19 Tubular retraction systems used in MIS, however,

enable the use of similarly sized incisions for all patients.

Shorter incisions minimise surgical cavity size, reduce soft-tissue

trauma, and produce an instrument-only surgical field, reducing

complications experienced by obese patients, including wound

infections.9,19 Excessive body weight also requires longer operating

times for open posterior lumbar spine fusion, but no significant difference

in operative times for MIS techniques, as the greater skin to

spine distance does not require additional dissection time when

using minimally invasive tubular retractor systems.19 These advantages

indicate the use of MIS in obese patients (Fig. 14).

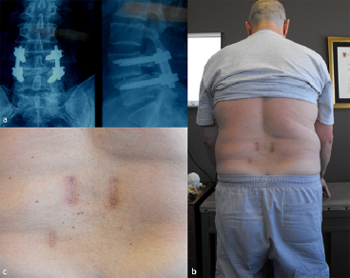

5.5.1. Illustrative patient 5

A 59-year-old male presented with mechanical back pain, unilateral

L5 radiculopathy due to lateral recess stenosis and an elevated

body mass index. MIS–transforaminal lumbar interbody

fusion (TLIF) was recommended to avoid a lengthy incision and

prolonged hospital stay. Surgical time was 4 hours and 50 minutes

with 240 mL of blood loss. LOS was 3 days. Frameless stereotaxis

was used to assist with percutaneous pedicle screw placement.

5.6. Revision surgery

Revision surgery is often more technically challenging because

of local scarring and greater complication rates such as nerve root

injury and incidental durotomy. Along with altered anatomy, absent

bony landmarks and limited surgical exposure, it is no surprise

that surgeons avoid MIS approaches for revision surgery.8,9

Fig. 14. Illustrative patient 5, 59-year-old, 135 kg male, who presented with

mechanical back pain, unilateral L5 radiculopathy due to lateral recess stenosis and

an elevated body mass index who underwent a transforaminal lumbar interbody

fusion (TLIF). (a) Left – anterior/posterior (AP) image intensifier (II) radiograph, and

right – lateral II radiograph showing L4/5 TLIF plus pedicle screw fixation; (b) 6-

month post-operative photograph of the patient standing; (c) close-up of 4 cm

bilateral incision, plus bone graft harvest, scars.

Lumbar interbody fusions are indicated for revision surgery of

recurrent disc herniation and post-laminectomy instability. Selznick

et al.'s study8 of 43 patients who underwent minimally invasive

posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) or TLIF, compared the outcomes following primary surgery to revision surgery at a prior

operative level. The primary surgery group consisted of 26 patients

undergoing operations for degenerative spondylolisthesis and

spondylolysis, degenerative scoliosis. The revision surgery group

consisted of 17 patients with the primary indications for the surgery

being post-laminectomy instability and multiple recurrent

disc herniations. They concluded that minimally invasive lumbar

interbody fusion is a possible option for revision surgery, without

significantly higher rates of blood loss, transfusion, infection or

neurological complications compared to primary surgery. However,

minimally invasive revision lumbar interbody fusions had

significantly higher complication rates, with the risk of inadvertent

durotomy and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak approximately six

times higher than in the primary surgery cohort. All CSF leaks were

fixed intra-operatively without developing into a pseudomeningocele

or requiring further surgery.8

Fig. 15. Illustrative patient 6, a 48-year-old male who presented with ongoing back

pain and evidence of a non-union following a L5/S1 stand-alone posterior lumbar

interbody fusion (PLIF). (a) Lateral image intensifier (II) intra-operative radiograph

showing pedicle screw fixation and posterolateral graft. (b, c) Intra-operative

photographs showing completion of procedure prior to removal of tubular dilators.

(d) Post-operative photograph at 10 weeks showing previous midline incision and

bilateral revision fixation using minimally invasive surgery.

It is recommended that surgeons gain substantial experience

with MIS techniques of primary patients, before attempting minimally

invasive revision interbody fusion of the lumbar spine.8,9

Surgeons attempting minimally invasive revision surgery

(Fig. 15) should also be ready to convert to wider exposures if necessary,

for safe exposure of the relevant spinal region.9

5.6.1. Illustrative patient 6

A 48-year-old male presented with ongoing back pain and evidence

of a non-union following a L5/S1 stand-alone PLIF. Revision

fusion with percutaneous pedicle screws and on-lay bone graft

over the L5/S1 facet joints was recommended. Operating time

was 1 hour, 40 minutes with 100 mL of blood loss. LOS was 3 days.

Significant immediate reduction in mechanical back pain was

experienced, with return to work within 6 weeks.

5.7. MIS grafting

Autografts involve transferring bone within the same individual.

20 Throughout the 1990s, as spinal fusion rates rose, bone graft harvests were most commonly used for spinal arthrodesis.21,22

With fusion, the gaps between host bone and graft fill via new bone

formation and with more bone deposition and remodelling on the

osteoconductive matrix, segmental stiffness increases. Thus, spinal

bone grafting is a race between fusion healing and failure of internal

fixation to immobilise spinal elements.20

Fig. 16. Illustrative patient 7, a 72-year-old female who presented with neurogenic

claudication and L4/5 grade 1 spondylolisthesis. (a) Intra-operative photograph

showing the minimally invasive surgery grafting technique for a posterolateral

graft. (b, c, d) Lateral intra-operative image intensifier radiographs showing (b) drill

preparation of facet joints; (c) insertion of graft packing tube; and (d) position of

posterolateral graft. (e) Axial post-operative CT scan with graft overlay on facet

joint.

An adequate blood supply is necessary to encourage healing.

Excessive muscle stripping and devascularisation limits oxygen,

nutrient, neovascularisation and cellular migration to the fusion

mass. Significant muscle necrosis may also provide environments

suitable for bacterial growth, which compete for nutrients and

interfere with the inflammatory processes necessary for the developing

fusion mass, thus causing graft failure.20 MIS, which aims to

minimise blood loss, muscle stripping and necrosis thus promotes

successful fusion (Fig. 16). With the limited number of studies

available, however, it is suggested that evidence based medicine

guide the use of bone grafts and bone morphogenic protein in minimally

invasive spinal fusion.13

5.7.1. Illustrative patient 7

A 72-year-old woman presented with neurogenic claudication

and L4/5 grade 1 spondylolisthesis. Decompression and posterolateral

onlay fusion was recommended. Interbody fusion was not

recommended due to poor bone mineral density. Following a midline

MIS decompression, percutaneous pedicle screws were inserted

and postero-lateral bone graft onlay was performed via

the retraction tubes for the pedicle screw system.

5.8. Emerging technology

Despite the benefits of MIS fusion in well-selected patients,

there are limitations which include: accelerated adjacent level

degeneration, symptomatic pseudoarthrosis and graft site morbidity.

22,23 Motion sparing techniques now offer improved stability

and intersegmental motion compared to current fusion operations,

24,25 following procedures for degenerative disc disease,

spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis.22,23,25 This allows surgeons

to avoid the aforementioned limitations, while treating patients

at earlier stages of degeneration than traditional fusion. Furthermore,

motion-sparing techniques like pedicle screw-based systems can be inserted via minimally invasive paraspinal techniques, thus

avoiding significant muscle and ligament damage.23

Fig. 17. Illustrative patient 8, a 54-year-old male who presented with mechanical

low back pain secondary to L4/5 facet joint arthrosis with a mobile spondylolisthesis,

resistant to multiple conservative therapies. Pedicle screw based motion

sparing techniques showing: (a) lateral image intensifier (II) radiograph showing

instability on flexion (left) and extension (right) views at L4/5. (b) Radioisotope

bone scan uptake at L4/5 facet joints. (c) Final intra-operative lateral II view of

Dynamic Stabilization Systems (DSS™, Paradigm Spine, Wurmlingen, Germany)

implant system. (d) Intra-operative photograph showing tubular dilators.

Although similar to rigid pedicle screw systems, posterior dynamic

stabilisation (PDS), including pedicle screw-based stabilisation

(Fig. 17), aims to relieve pain, other compressive neurological

symptoms, and restore stabilisation by re-establishing the natural

anatomic position and enabling restricted segmental motion.22,23

In contrast to fusion systems that aim to withstand loading until

fusion occurs, pedicle screws in dynamic stabilisation systems

need to withstand cyclical loading indefinitely, which makes the

screws prone to loosening.22

As the PDS technology has only recently emerged, the available

literature is sparse with most studies having only 2 years of followup

at most.24,25 Furthermore, it may take 5 years to 10 years before

the beneficial effects of PDS, like adjacent segment degeneration,

can be detected when compared with rigid forms of spinal fusion.

Thus, multiple, similarly designed trials need to be undertaken before

any conclusions about the benefits of PDS over current fusion

techniques can be drawn.25

5.8.1. Illustrative patient 8

A 54-year-old male presented with mechanical low back pain

secondary to L4/5 facet joint arthrosis with a mobile spondylolisthesis,

resistant to many years of multiple conservative therapies.

A posterior, motion-sparing dynamic stabilising implant was offered

as an alternative to fusion. The operating time was 2 hours,

25 minutes with 110 mL of blood loss. Follow-up at 3 months revealed

no instability on flexion/extension radiographs with moderate

reduction in low back pain scores.

6. Discussion

Since 2000, the techniques of minimally invasive spinal fusion

have improved substantially. With increasing experience, indications

for minimally invasive spinal fusion have expanded.4,10 Currently,

indications are similar to those for open surgery and

strongly rely on the surgeon's experience with the procedure.14

Most MIS spinal techniques have steep learning curves, requiring

different cognitive, psychomotor and technical skills.6,9,13 It is recommended that surgeons have adequate experience with open

procedures before attempting minimally invasive methods14 and

that they begin with simple MIS procedures. Depending on the

procedure, the patient and the surgeon's experience, MIS may take

more time to perform than open surgery.9

As indications for percutaneous pedicle screw techniques expand,

the nuances of the MIS technique will also expand. It is paramount

that experienced surgeons share their collective

knowledge to assist surgeons at their early attempts of these complex,

and potentially very dangerous procedures.

MIS aims to minimise surgery-associated risk and morbidity,

including irreversible muscle injury from muscle stripping and

retraction, which are associated with poor clinical results, while

achieving the same results as conventional approaches.6,8,10,16 Despite

encouraging clinical results, MIS techniques are in their infancy

with the results being preliminary at best. Prospective

outcome studies with long-term follow-up comparing new minimally

invasive spinal fusion to conventional open fusions are required

to ultimately determine the safety, effectiveness and

clinical benefit of minimally invasive spinal fixation.4,5,17

7. Conclusion

Spinal fusion is the gold standard in maintaining the stability of

unstable spinal segments for multiple potential pathologies. As the

techniques and instruments in MIS spinal surgery have evolved,

the indications for minimally invasive spinal fusion have expanded

to include: degeneration, trauma, deformity, infection and neoplasia.

With technological advancements, it is expected that MIS fusion

techniques will become a prominent part of spinal surgery

and that indications for minimally invasive spinal fusion will expand.

This review adds to the literature to inform prospective surgeons

of the nuances of the percutaneous technique for pedicle

screw insertion.

References

- Kanter AS, Mummaneni PV. Minimally invasive spine surgery. Neurosurg Focus

2008;25:E1.

- Mayer HM. A new microsurgical technique for minimally invasive anterior

lumbar interbody fusion. Spine 1997;22:691–700.

- Harris EB, Massey P, Lawrence J, et al. Percutaneous techniques for minimally

invasive posterior lumbar fusion. Neurosurg Focus 2008;25:E12.

- Hsieh PC, Koski TR, Sciubba DM, et al. Maximizing the potential of minimally

invasive spine surgery in complex spinal disorders. Neurosurg Focus 2008;25:

E19.

- Lipson SJ. Spinal-fusion surgery – advances and concerns. N Engl J Med

2004;350:643–4.

- Kan P, Schmidt MH. Minimally invasive thoracoscopic approach for anterior

decompression and stabilization of metastatic spine disease. Neurosurg Focus

2008;25:E8.

- Assaker R. Minimal access spinal technologies: state-of-the-art, indications, and

techniques. Joint Bone Spine 2004;71:459–69.

- Selznick LA, Shamji MF, Isaacs RE. Minimally invasive interbody fusion for

revision lumbar surgery: technical feasibility and safety. J Spinal Disord Tech

2009;22:207–13.

- Kerr SM, Tannoury C, White AP, et al. The role of minimally invasive surgery in

the lumbar spine. Oper Tech Orthop 2007;17:183–9.

- Beisse R. Endoscopic surgery on the thoracolumbar junction of the spine. Eur

Spine J 2006;15:687–704.

- Foley KT, Holly LT, Schwender JD. Minimally invasive lumbar fusion. Spine

2003;28:S26–35.

- Foley KT, Gupta SK. Percutaneous pedicle screw fixation of the lumbar spine:

preliminary clinical results. J Neurosurg 2002;97(Suppl. 1):7–12.

- Oppenheimer JH, DeCastro I, McDonnell DE. Minimally invasive spine

technology and minimally invasive spine surgery: a historical review.

Neurosurg Focus 2009;27:E9.

- Holly LT, Schwender JD, Rouben DP, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal

lumbar interbody fusion: indications, technique, and complications. Neurosurg

Focus 2006;20:E6.

- Regan JJ, Yuan H, McAfee PC. Laparoscopic fusion of the lumbar spine:

minimally invasive spine surgery. A prospective multicenter study evaluating

open and laparoscopic lumbar fusion. Spine 1999;24:402–11.

- Smith JS, Ogden AT, Fessler RG. Minimally invasive posterior thoracic fusion.

Neurosurg Focus 2008;25:E9.

- Swanson AN, Pappou IP, Cammisa FP, et al. Chronic infections of the spine:

surgical indications and treatments. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;444:100–6.

- Cowan JA, Thompson BG. Neurosurgery. The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2010.

Chapter 36.

- Rosen DS, Ferguson SD, Ogden AT, et al. Obesity and self-reported outcome

after minimally invasive lumbar spinal fusion surgery. Neurosurgery

2008;63:956–60.

- Vaccaro AR, Chiba K, Heller JG, et al. Bone grafting alternatives in spinal

surgery. Spine J 2002;2:206–15.

- Sandhu HS, Grewal HS, Parvataneni H. Bone grafting for spinal fusion. Orthop

Clin North Am 1999;30:685–98.

- Meyers K, Tauber M, Sudin Y, et al. Use of instrumented pedicle screws to

evaluate load sharing in posterior dynamic stabilization systems. Spine J

2008;8:926–32.

- Bertagnoli R, Fantini GA, Brau SA, et al. Spinal motion preservation technologies:

surgical approach and procedure. Chapter 22. In: Nucleus arthroplasty. Volume

IV: Emerging technologies. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Raymedica; 2007. p. 7–14.

Available from: http://www.thesona.com/V4_V5-Final.pdf.

- Heary RF. Dynamic stabilization. Neurosurg Focus 2010;28:E1.

- Bono CM, Kadaba M, Vaccaro AR. Posterior pedicle fixation-based dynamic

stabilization devices for the treatment of degenerative diseases of the lumbar

spine. J Spinal Disord Tech 2009;22:376–83.

Technique, Challenges and Indications for Percutaneous Pedicle Screw Fixation Technique, Challenges and Indications for Percutaneous Pedicle Screw Fixation

You will need the Adobe Reader to view and print the above documents.

|